Subtle Democracy: Public Pedagogy and Social Media

Joannah Portman-Daley

Introduction

On September 30, 2010, Malcolm Gladwell argued that in the midst of our evangelic enthusiasm for social media the real definition of activism seems to have been forgotten. His widely debated New Yorker article “Small Change” draws upon a 1960s sit-in in North Carolina that began with the refusal to serve four black students at a Woolworth’s and ended in a protest that spread throughout the entire South, crossing state lines and including both black and white protesters. Gladwell argues, “these events in the early sixties became a civil-rights war that engulfed the South for the rest of the decade—and it happened without e-mail, texting, Facebook, or Twitter” (“Small Change”). Claims that social media can inspire a revolution, he posits, are grandiose assertions from solipsistic individuals who, while marveling at their technological innovations, seem to have forgotten the history of communication. Real activism, Gladwell seems to be saying, depends on deep, tight ties, whereas “the platforms of social media are built around weak ties.” For Gladwell, Facebook friendships and other similar social networking relationships cannot support and sustain high-risk activist agendas the way groups of people who know each other physically and see first hand one another’s commitment to a cause can. Gladwell argues social media allows only for participation, and not for the sacrifice he identifies as an integral component of “real” activism (“Small Change”). While discussing Gladwell’s argument the next day in an online New York Times comment thread, one contributor took his idea of sacrifice even further by claiming that “being an activist involves being killed. It involves putting your body on the line. It means presenting yourself physically, not on a web page. It means man-to-man confrontation. It means blood, sorry, and pain” (Alan).

A few days later, Brittany McMillan, a Canadian teenager, sent out a worldwide request via her Tumblr account asking for the creation of a national lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Spirit Day. Responding to recent suicides of gay youth such as Tyler Clementi, her goal was to “stop the hate,” and she requested that all supporters of her movement wear purple clothing on October 20, 2010, to raise awareness for her cause. According to the Facebook event page she created, “Purple represents Spirit on the LGBTQ flag and that’s exactly what we’d like all of you to have with you: spirit. Please know that times will get better and that you will meet people who will love you and respect you for who you are, no matter your sexuality.” Through Facebook, McMillan garnered hundreds of thousands of followers in only a matter of hours. Her efforts crossed not only state lines but also international ones, and her supporters were of all races, ethnicities, and sexual orientations. Even so, it seems that due to her lack of “sacrifice,” and the simplicity of the clicking action required by her supporters, neither Gladwell nor the Times commentator would likely consider her efforts effective activism.

Just over a year later, in December of 2011, the Arab Spring broke out in Egypt and across the Middle East. Activists rose up against regimes in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Yemen using social media tools as a key element in their organizing efforts—and with no lack of sacrifice in their struggle. Of course, these citizens engaged in all types of traditional activism, but the information they shared and learned across social media was instrumental to their success. These platforms allowed citizens to exchange information while circumventing government restraints as they “brainstormed on the use of technology to evade surveillance, commiserated about torture and traded practical tips on how to stand up to rubber bullets and organize barricades” (Kirkpatrick and Sanger 2011). Still, in “Does Egypt need Twitter?”, Gladwell contends that these tools are unexceptional, arguing that how the citizens revolt is less interesting than why.

The definition of what counts as civic or political activism in the digital age is still being widely debated. The rise of Web 2.0, and the social media-based tools that have accompanied it, generate several grey areas. While most critiques do not go so far as to insist upon bloodshed as a definitive component of activist behavior, some agree with Gladwell that social media is not the place for “real” engagement. Instead, they cling to traditional notions of civic involvement and activism—such as voting, donating, attending rallies, protesting, and the like—discounting newer, digital approaches. To this end, they have labeled many student-activists, most of whom are members of the “net generation,” as “slacktivists,”[1] and they argue that while these new “digital citizens” may strive to appear politically or civically active—by joining Facebook groups, for example—they actually understand little about their actions and contribute nothing to the cause at hand (see Tapscott Grown Up; Bauerlin; boyd “Can Social Networks Enable”). However, it is perhaps this strict notion of civic engagement and the rhetoric that supports it that keeps young people, who often tend to be the most avid new technology users, from realizing their potential as citizens, and by extension, realizing the potential of social media for civic activism. This is especially true when their digital activism occurs in informal and extracurricular ways that aren’t tied to an explicit or traditional educational or activist purpose and are primarily used in personal downtime.

In an attempt to unpack the capacity and potential of social media for civic and political purposes, this article draws upon data collected from a larger qualitative study of interviews I conducted with members of the net generation over the course of six months in 2010. My IRB-exempt study was carried out with the intention of examining the differences between varying citizenship styles (for example, traditional or “dutiful” versus digital or “self-actualizing,” see: Bennett) and definitions of civic action in the digital age. It consisted of collecting and analyzing the online behaviors of ten student activists who completed interviews, recorded time-use diaries, and collected screen captures of their social media usage. From this data, the concept of public pedagogy—the teaching and learning that occurs in digital spaces outside of traditional educational settings—emerges as a tract where we can witness how the informal learning that occurs within public spaces leads to the spread of civic engagement and maybe even political power (Sandlin; Giroux). Specifically, Henry Giroux argues a lack of attention to the pedagogical implications of such extracurricular or informal tools and spaces keeps digital critics, like Gladwell, from recognizing that new media tools can influence both the values that motivate activism and the circumstances that allow it (“The Crisis of Public Values” 22).

In the following sections, I begin by offering examples and analyses of several of my net generation participants’ informal contributions to, and engagements with, various public pedagogies within and across multiple social media spaces with the aim of demonstrating the significance of seemingly inconsequential actions. Next, I offer the example of a particularly aberrant participant, Cal, who offers a fine example of what I will call a “realized digital citizen” in the sense that he is aware of and takes full advantage of public pedagogy for civic and political purposes. Finally, I aim to situate the parameters and power of an activist, social media-based public pedagogy in terms of user participation to illustrate how networked technologies encourage a reconsideration of what it means to be an activist, and what may, or may not, count as activism in the digital age.

Digital Engagement Research

As alluded to earlier, the primary sources for this study are the extracurricular digital writing practices and social media spaces inhabited by ten students of the net generation. To recruit my participants, I targeted civically or politically based student organizations, attended their meetings, explained my study, and asked for interested volunteers. Such organizational affiliations allowed the study to gauge if and how these students recognized their informal digital action alongside their more traditional, face-to-face efforts. I contacted nearly a dozen student organizations, but chose to work with the following five: College Democrats, College Republicans, National Society of Women Engineers, National Society of Black Engineers, and Student Action for Sustainability. Decisions were based on the responsiveness of organizations and their diversity in relation to one another.

The data referred to comes from the interviews, time-use diaries, and screen captures of five (of the study’s ten) specific students. After obtaining a signed informed consent, I spent an hour interviewing each student activist about his or her personal civic involvement, that which takes place via out-of-school digital literacy practices apart from his or her organization. In addition to the interview, I asked each participant to complete a time-use diary for one week.[2] The diaries I provided asked participants to record the date, time, and description of their social media activity, as well as to offer commentary on whether they thought it counted as civic engagement or activism. The entries provided a complement to the interview process by filling in gaps left by participants when trying to recall the details of their digital activity, as well as by accounting for the activities that occurred on their own time. Based on the information that emerged in the interviews and time-use diaries, I took screen captures of and analyzed the social media spaces the students inhabited. These spaces consisted of social networking sites (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc.), social news sites (Digg, Reddit), and social bookmarking sites (StumbleUpon).

The five student activists who appear in this article—Cal, PJ, Gabrielle, Michelle, and Christina—best represent the wide range of feelings, understandings, and actions relating to civic engagement and public pedagogy held by the group of ten as a whole. The students’ names have been changed to protect their privacy. I will turn first to Gabrielle.

Gabrielle

Gabrielle, a 20-year-old Haitian-American junior and active member of the National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE), spends a self-reported nine to ten hours a day online. Unlike the more Facebook-obsessed members of her generation, she is an avid tweeter. She spends hours upon hours on Twitter tweeting what she describes as “quotes to open peoples [sic] minds.” Gabrielle keeps a file of quotes in her BlackBerry that she calls upon when the appropriate mood or moment strikes and even enters quotes from friends mid-conversation if she finds them inspirational. She does so with the aim of “making people think more” or “making them feel better.” In fact, it is so important that she share these quotes with others, she went to the length of installing an app on her phone that allows her to tweet during her 45-minute bus commute to campus without having to pay for Internet access.

In addition to sharing inspirational quotes and information, Gabrielle says she learns a lot on Twitter, especially through the site’s trending topics. For example, a hot trending topic during Gabrielle’s interview was the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. As a Haitian-American, Gabrielle was particularly interested in keeping up-to-date on news surrounding the earthquake’s devastation and she believed Twitter was the best way to do so. In line with Gabrielle’s usage, a 2010 study that gauged the information-sharing capabilities of Twitter demonstrated that over 85 percent of all trending topics, which are determined by the most popular subjects tweeted about in a given time period, are either breaking or persistent news topics (Kwak, Lee, Park, and Moon 1). According to Gabrielle, these topics both help inform her of what is going on in the world and help her to inform others through her retweets of or comments on trending topics.

PJ

Like Gabrielle, PJ shares quotes with friends via Twitter and does so in a manner he considers non-biased and “eye-opening.” PJ is a 22-year-old Nigerian senior and also a NSBE member. He says, “everyone has their own opinions so I‘ll try not to make [my tweets] so opinionated.” PJ sees tweeting (and retweeting) as a way to inform others of events and perspectives he considers important and also a way to let them choose their own path in terms of what they want to know. Instead of “telling people how it is,” PJ would rather post something and let friends check it out if they want to. As he explains, “a lot of times it’s not about being right or wrong but understanding where another person is coming from.” He strives for inspiration in his quotes and says their main purpose is to “help people look at life and understand life in a different way.” For PJ, such inspiration comes from influences as disparate as Bob Marley, President Obama, Tupac, and Shakespeare.

Michelle

Michelle is a 21-year-old Caucasian junior, a member of the environmental group Student Action for Sustainability (SAS), and another avid retweeter. She follows numerous celebrities who promote environmental causes through Twitter by posting links or updates about various activist efforts and initiatives. Michelle claims to learn a lot through these tweets and likes to share the newfound knowledge with her followers. As an example, Michelle recalls recent Twitter activity in which she retweeted an image of a baby sea bird that had consumed plastics littering our oceans. The graphic image, she suggests, spoke louder than any words could have. Upon seeing the photo, many of her followers agreed.

On the surface, retweeting might seem like little more than email forwarding. However, in “Tweet, Tweet, Retweet: Conversational Aspects of Retweeting on Twitter,” danah boyd, Scott Golder, and Gilad Lotan argue it should be seen as something far more than that. As they contend, “retweeting can be understood both as a form of information diffusion and as a means of participating in a diffuse conversation. Spreading tweets is not simply to get messages out to new audiences, but also to validate and engage with others” (1). In this regard, while the primary purpose of retweeting may be to spread information, it also promotes various kinds of “social action.” Calls to protest and donate fall into this category, as do tweets that exhibit a “demonstration of collective group identity-making” (boyd et al.). Indeed, by tweeting and retweeting, Gabrielle, PJ, and Michelle acknowledge that they are banding together with others and, though they don’t say as much, their descriptions of why they retweet suggest that their retweets are a subtle creation of community. Furthermore, these student activists are focused on gathering and distributing knowledge contextually, which suggests not only a rhetorical awareness and savvy but also a critical attention to, and understanding of, material conditions—all for the betterment of themselves and others. And these retweets may actually be reaching far more people than they even realize. As Kwak, Lee, Park, and Moon note, “a closer look at retweets reveals that any retweeted tweet is to reach an average of 1,000 users no matter what the number of followers is of the original tweet” (1).

When I point out how the information she tweets ultimately works to better her community by informing fellow users in useful ways, Gabrielle simply shrugs and mutters an “I guess,” before insisting that she “should be doing more volunteering and doing community service, lending a hand to other people” in order for her actions to constitute “real” engagement or activism. Gabrielle dismisses her online activity—activity that actually does lend a hand, so to speak—and remains tied to traditional, face-to-face notions of making a difference, ones that demand physical, face-to-face presence, like volunteering and rallying in the quad at her university. Even her use of “lending a hand” stresses a physicality that furthers her reliance on traditional involvement. She cannot seem to accept the value of her digital efforts because she insists that real engagement or activism would “take lot of [her] time, and [she] wouldn’t really be getting anything back for it, but the starting and ending points would be different,” a definition she says she gained from community service performed through her high school and that was reinforced by both the media and freshman orientation at her university. Interestingly, this definition seems in line with Gladwell’s argument that real engagement hinges on the concept of sacrifice rather than participation and ignores, or undermines, any reciprocal or pedagogical gain (“Small Change,” “Does Egypt Need Twitter?”). Gabrielle’s perspective forces her to consider her Twitter activity as slacktivist (rather than activist), even though it holds civic value.

Similarly, because Michelle considers herself a “follower rather than a leader” in the sense that she leans on retweeting rather than finding her own information to post, she doesn’t consider herself to be as engaged or active as she could be. In fact, Michelle describes her friend Wendy, president of SAS, as the most digitally engaged person she knows precisely because “Wendy goes out and finds information and puts it on her [Facebook].” Michelle explains, “Someone else may read it and repost it, but they aren’t going out and finding it like Wendy.” Michelle recognizes herself as a reposter of much of Wendy’s content, and thereby a less active digital citizen since her role requires less effort. Like Gabrielle, Michelle also uses words like “hand,” and other metaphors of bodily presence, to stress the difference between what she considers her lack of real engagement and someone else’s more robust involvement implying, at least, an unconscious reliance on a traditional understanding of the engagement involving physicality. For Michelle, her activity isn’t necessarily engaged because it doesn’t have a “direct hand” and doesn’t “take a leadership role” in the cause.

Despite how active and engaged their digital activity proved to be, both Gabrielle and Michelle appear tethered to normative notions of what comprises a citizen and what counts as “activism.” Both student activists seem to have shaped their ideas of “real engagement” from past classroom projects or other institutional experiences that conveyed the sense that anything civic is hard work—hard work that demands a sense of obligation, a top-down organization, without reciprocity. Because Michelle and Gabrielle both consider contributing to Twitter an everyday, effortless pastime and one they engage in with peers (as well as actually enjoy), they have difficulty viewing the activity as civically meaningful.

While Gabrielle and Michelle rely on traditional understandings of activism to define their social media actions, PJ is more open to new conceptualizations of the term. When it comes to activism, he says he tries to focus less on the results and more on the actions themselves. In terms of measurement, he admits he views comments on his Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube posts as a way to gauge the effect of his actions, but insists that one can’t focus on such things too much. He thinks it’s enough to intend to “help” someone. Help, for PJ, means improving another person’s life in some manner. He claims “help” is the aim of his posts and he trusts that it will be the inevitable outcome; he says that when he writes something on social media he doesn’t feel the need to receive a comment back. For him, it’s enough to know that what he wrote will “hit someone somewhere.” Using this mindset, PJ attempts to move away from his history of traditional service with organizations such as Campus Crusade for Christ and Jumpstart and, instead, embraces the immeasurable nature of his many social media endeavors. With those traditional organizations, PJ spent time volunteering in literacy and ecclesiastical efforts inside his community. Working face-to-face allowed him to see the direct effects of his actions, while social media, he acknowledges, doesn’t always offer such confirmation. PJ struggles with the fact that online he often could not see tangible results, but the following analogy helps him persist:

“Let’s say I donated shoes to an organization, and I wrote stay in school on the shoes and I see some kid wearing them, that’s icing on the cake where I see the results head on. But if I don’t see it, it doesn’t mean I’m not helping someone out. It just means I didn’t see the results.”

To PJ, measurement doesn’t dictate worth, regardless of whether it is tied to a face-to-face or online activist agenda. His intent is to help, and to him, actions that carry intent count as civic engagement, especially in the digital age.

At the turn of the century, Henry Jenkins and David Thorburn anticipated these conflicted understandings of citizenship and activism engendered by digital spaces, arguing that digital democracy would be “decentralized, unevenly dispersed, even profoundly contradictory” and that the effects would first appear in cultural forms, “through a changed sense of community” and “a citizenry less dependent on official voices of expertise and authority” (2). The student activists’ social media-based action described in this article illustrates the development of such cultural forms of citizenship—a changed sense of community and a public focused primarily on peer-to-peer knowledge exchanges—even if their understandings of civic activism have not kept pace. Indeed, the above examples of each student activist’s digital writing activity offers instances of everyday actions that can be considered civic contributions to a public pedagogy in the sense that they share information with the intention of helping others—regardless of whether or not the results are quantifiable. In the next section, I will discuss how because many of the actions are so everyday—and so informal—that they are more difficult to accept as real and meaningful, but in our newly digitized world they constitute valuable social action.

Public Pedagogy and the Problem of Informality

There was agreement amongst Gabrielle, Michelle, PJ, and all the other student activists in my study that staying informed is not only a key element of civic engagement, but in fact the most important element. The idea of public pedagogy is consistent with this notion. Public pedagogy consists of teaching and learning, not only from others, but also from oneself in a public space—something that exists outside of institutional walls (Sandlin; Giroux; Hayes and Gee). Despite the fact that these student activists believe that staying informed is one of the most significant duties of good citizenship, their digital learning and information sharing didn’t seem to count for most of them as “civic action,” a fact that illustrates the “profoundly contradictory” nature of digital democracy that Jenkins and Thorburn forecasted. Furthermore, the service of public pedagogy never occurred to these young students, or if it had, the idea held little civic merit, which was particularly surprising considering their overwhelming online activity. They reported daily usage times ranging from three to ten hours, much of which consisted of activities where they shared information in a manner that taught someone useful facts or where they gained important knowledge from information shared by others. When I explained the ideas behind public pedagogy, most of the students came to see its merit but were again hesitant to admit that it was “real” learning or teaching—precisely because, for them, it wasn’t related to a traditional, classroom-based agenda. Gabrielle explained that it was hard for her to think of social media as a worthwhile platform for teaching or learning because so few of her teachers have used it in their classrooms.

The term “pedagogy” naturally invokes images of classroom-based curricula in conventional schooling models, so it is hard to blame students for their limited interpretation. However we can blame educators for promoting this view. As Elizabeth Hayes and James Paul Gee note, even with the breadth of scholarship seeking to enhance traditional understandings of pedagogy, public pedagogy is not taken as seriously as it should be (“Public Pedagogy”). Though many scholars acknowledge the power of informal learning, the importance of the teaching component is less accepted. As Jennifer Sandlin writes in her Handbook of Public Pedagogy, “people tend to contrast informal learning with school learning in terms of teachers and teaching, claiming that informal learning does not involve teaching or, at least, that teaching is not a predominant feature of informal learning” (2). Moreover, some educators still fear the disruptive nature of the Internet on students’ time and the results of their work, especially in terms of trusting information, considering reliable sources, and plagiarism. Gabrielle, PJ, and Michelle confirm this fear, stating what they learned about digital technology from formal educators centered on how to be critical of said technology (i.e., not using Wikipedia as a “reliable” source), not necessarily on how to use it. Subsequently, they are left to use social media primarily in their downtime. While students tend to use the platforms productively, Mark Pegrum argues that when left unguided, the directions extracurricular usage can take are not always productive in traditional terms, which is why many educators fail to see a link to effectiveness in the classroom (Blogs to Bombs). After all, it is often gratuitous or dangerous social media usage that garners newsworthy attention. In actuality, however, Hayes and Gee assert that much of the popular culture that permeates social media spaces “teaches 21st-century skills like collaboration, producing and not just consuming knowledge, technology skills, innovation, design and system thinking, and so forth, while school often does not” (188).

Clinging to the informal/formal learning binary and failing to recognize the more progressive roles and implications of pedagogy may be, in part, why the public pedagogy that takes place within these sites hasn’t generally been considered civic or political action. One of the reasons Gladwell dismisses social media (as a “real” means for engagement) is that he doesn’t account for any of its pedagogical implications. In a 2011 essay, Henry Giroux responds to Gladwell’s dismissal by arguing that the pedagogical implications of technological advances, like social media, fundamentally influence democratic ideals and actions:

While Gladwell is right to be suspicious of any wild utopian claims for the Internet and new media, he fails to address the pedagogical role the new media can play in producing a formative culture that makes social action possible . . . he fails to even remotely understand the educational value of such media in creating the formative culture and public values that might enable such action to happen. (Giroux “The Crisis of Public Values” 22)

Henry Giroux’s work on public pedagogy not only validates the legitimacy of informal learning, but also insists that the notion of public pedagogy is vital to our re-shaping democratic values and conceptions of what it means to be civically or politically minded. According to Giroux, “pedagogy, at its best, implies that learning takes place across a spectrum of social practices and settings” and “culture now plays a central role in producing narratives, metaphors, and images that exercise a powerful pedagogical force over how people think of themselves and their relationships to others” (“Cultural Studies” 62). Furthermore, he draws on the work of philosophers such as C. Wright Mills, Raymond Williams, and Cornelius Castoriadis to stress how the connection between pedagogy and social change are now stronger than ever due to the means provided by new media and the Internet. Hayes and Gee suggest that the informal learning of public pedagogy in digital spaces offers the “potential for activism and resistance” (186). We might extend Hayes and Gee to argue the political impulse for critical thought, which public pedagogy promotes, is crucial for citizens to comprehend pre-established social orders and assert their claims on justice and democracy (Giroux “Living in the Age”).

Most of the social media practices in my study fall in step with the definition of civic engagement Thomas Ehrlich’s provides in Civic Responsibility and Higher Education (2000). Ehrlich defines civic engagement as “working to make a difference in the civic life of our communities and developing the combination of knowledge, skills, values and motivation to make that difference” (vi). He stresses the everyday nature of civic engagement: “it means promoting the quality of life in a community, through both political and non-political processes” (vi). Moreover, he argues, “a morally and civically responsible individual recognizes himself or herself as a member of a larger social fabric and therefore considers social problems to be at least partly his or her own; such an individual is willing to see the moral and civic dimensions of issues, to make and justify informed moral and civic judgments, and to take action when appropriate” (xxvi). Most of the student activists who participated in my study believed themselves to be responsible citizens who were actively engaged in efforts to make social change, but weren’t aware of how deeply invested they were in the medium of digital technology for the development of their knowledge, skills, values, and motivation.

In the next section, I will examine Cal, the one student in my study who serves as an example of what I will call a “realized digital citizen.” Cal’s realized status comes from the fact that, unlike Gabrielle and Michelle, and even PJ at times, he both understands his investment in digital technology and values it as a means for social change.

Realized Digital Citizenship

Cal, a 23-year-old Caucasian senior and Chairman of his university’s College Republicans, believes his online informal learning is more worthwhile than what he learns in the classroom. A closer look at Cal’s digital efforts, and his understanding of their role in his civic life, will help illustrate (along with Giroux and Gee’s thesis) the power of public pedagogy as a means for activism.

Cal spends most of his day online. He says he goes online the moment he “stumbles out of bed” and doesn’t get off until he goes to sleep. On a typical day he wakes up at 7 a.m., and before he drinks coffee or eats breakfast he takes a look at his favorite Internet news sites to see what’s happening. Like most of his generation, he eschews paper-based outlets in favor of online sources and, more specifically, peer-driven, social media-based news sources. According to the PEW Internet and American Life Project, Cal’s experience is hardly unique: “Eight in ten college-educated adult Internet users (81 percent) get news online and three in four college educated Internet users (75 percent) get political news online” (Lenhart, “Social Media and Young Adults”).

In our interview, Cal explains his concept of “flow information set,” which he uses to describe the sites he routinely visits. The flow goes something like this: Reddit, Facebook, Weather, Gmail, and The Drudge Report. The information Cal gives and receives on each of these sites contributes to sharing on the other sites, which, according to Hayes and Gee, should be considered a form of distributed knowledge—and a fundamental component of public pedagogy. Hayes and Gee describe this process of distributing knowledge as “knowledge that exists in other people, material on the site (or links to other sites), or in mediating devices (various tools, artifacts, and technologies) and to which people can connect or ‘network’ their own individual knowledge” (188). Such actions encourage greater use of dispersed knowledge and allow users to make individual rhetorical choices in regard to their information sharing.

Cal begins his daily process by checking Reddit, a social news site where all content is user-driven. Users post links to news stories, images, or videos, and other users create conversations around the content via commenting. Reddit allows users to participate in “subreddits” (subject categories) of their choosing, where they may read and write on specific topics. Subreddits include science, politics, technology, art, gaming, environment, and atheism, among others. There’s also a subreddit called “AskReddit,” which describes itself as a forum for “thought-provoking, inspired questions” where users can ask questions on any topic that interests them, and receive answers from other users.

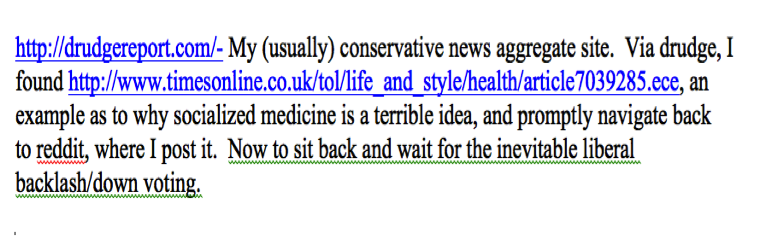

Typically, Reddit is a fairly left-leaning site, so I was surprised to learn that it was among Cal’s favorites. However, Cal sees his participation in Reddit, in a very general sense, as an educator. He feels it is his responsibility to provide alternate viewpoints to the mostly liberal news stories posted there. He explains that if he sees someone “bashing capitalism” he goes in and provides “another perspective.” And in doing so, Cal often shares knowledge he gains from the Drudge Report, the right wing news aggregator. Cal aims to produce a “balancing effect” by working to combat echo chambers, which he sees “happen a lot” (a common critique of information sharing within social networking sites). Indeed, according to boyd, when information is shared strictly among like-minded users, networks tend to create “cavernous echo chambers,” which can make it seem like an issue or an idea is gaining more traction than it truly is (“Can Social Networks Enable”). Figure 1 offers an example from Cal’s time-use diary of his back-and-forth between Reddit and Drudge.

Figure 1: Cal’s Time-Use Diary Entry

Figure 1: Cal’s Time-Use Diary Entry

Here, Cal explains how he posted an article about the negative aspects of socialized medicine (which he found on Drudge) to the Politics subreddit. His intention, he claims, was to balance the conversation by informing Reddit users of perspectives that exist outside of their like-minded forum. When conversation centers on consensus, it not only keeps users from being fully informed on a given issue, but also from realizing the need to take action.

After Reddit and The Drudge Report, Cal turns to Facebook. While he admits that he kills time on Facebook just looking at pictures, videos, and random postings, he differentiates his use of the site two ways. First, there is “downtime” activity, and then there are activities the site enables that he believes constitutes greater civic and political purposes. Cal describes Facebook as “indispensable” for civic and political organizing purposes. He uses it for posting announcements and calling meetings for the College Republicans, national political networking (such as preparing to attend to the annual Conservative Political Action Conference), and for posting strategic “status updates” he hopes will inform others of important news he thinks they might have missed and should be aware of. Cal tells me he considers himself both a teacher and a student in the broad sense of each term. One of the goals for his social media use is to “help people know what’s going on in the world,” so that they can “make a change for the better.” He says it “feels good to share this info,” and Facebook is the place to do it since, he points out, it is “definitely harder to go out onto the quad and yell my brains out.” Cal espouses the same beliefs about making a change by helping others through information sharing as Gabrielle, Michelle, and PJ. But because Cal recognizes such sharing as civically meaningful, he does more of it. His awareness breeds action.

When I asked Cal to provide examples of civic or political action in social media spaces, he gives me two nearly opposing examples. The first is obvious in the sense that it falls into traditional notions of civics, while the second is more obscure, precisely because of its everyday nature. Like Ehrlich, Cal doesn’t distinguish between the two, as both work to promote a quality of life in their respective communities. For his traditional example, Cal offers Wikileaks, which he argues is one of the best means for civic action in social media spaces. Founded by famed Internet activist Julian Assange, Wikileaks is a self-proclaimed not-for-profit media organization whose “goal is to bring important news and information to the public” in order to expose significant injustice around the world. It is a website where the average citizen, or “whistleblower,” can anonymously post insider information that, in Cal's words, “uncovers more news stories than the Washington Post.” For Cal, Wikileaks is a prime example of how social media enables and encourages online civic action.[3] Interestingly, what makes this hybrid activist/news media site so successful is, in fact, the weak ties that Gladwell argues against (“Small Change”). Wikileaks thrives on strangers electing to copy all of its data onto their personal computers. The more copies that exist between random, loosely-tied users, the harder it is for governments or other organizations to stop the dissemination of the site’s content. If the site operated on the strong ties Gladwell insists are necessary for real activism—those that exist between people who know and trust each other well and are obviously committed to the same issue—it would be far easier for authorities to locate information and therefore easier to shut down the operation.

Of course, Wikileaks is an obvious example of civic action in the sense that it is directly tied to traditional notions of politics and protecting transparency in government. However, as Giroux insists, there are less obvious examples, ones that aren’t tied explicitly to civic or activist causes but are more personal or social in nature, yet still productive. These personal or social examples range from bringing people together on social networks to posting views in a critical or informative manner (“Crisis of Public Values” 22). In our interview, Cal offered a personal example that fell directly in line with Giroux’s analysis. As Cal tells the story, on AskReddit a user solicited advice on how to hike the Appalachian Trail. Cal had some experience hiking the trail and provided advice that would save inexperienced hikers “a lot of pain.” Without the information, Cal says, the user would have been in for a far longer, and potentially dangerous, trip. In Cal’s view, this kind of informal information sharing is entirely commonplace. And to him, it is just as important in many ways as what occurs on Wikileaks. While others might not view such content as civic engagement or activism, it can be argued that this kind of informal information sharing positively affects community in small ways.

Cal’s example of informal public pedagogy offers a more personal, everyday kind of information exchange—much like the ones Gabrielle, Michelle, and PJ described. Its focus on helping communities through a variety of means falls in line with Ehrlich’s definition of civic engagement, which stresses “promoting the quality of life in a community, through both political and non-political processes” (iv) and sounds a lot like PJ’s understanding of “help.” Cal’s definition of civic engagement, which he admits is “a pretty broad term,” stresses the same sentiment, as it includes “anything from street protests (direct) form to just being informed—having an informed conversation with another on a specific subject.” Like the other participants, Cal sees “informing oneself and others” as not just an important act of civic engagement, but as the most essential one.

Twitter, Reddit, Facebook, and other social media sites provide opportunities for civic engagement by offering access to information like no means of communication before them. As Cal points out, the “subtle hand of the Internet adds a whole new dimension to activism; it has democratized information.” Interestingly, like both Gabrielle and Michelle, Cal also turns to physical, bodily metaphors in his description of what constitutes real engagement or activism. However, while Gabrielle and Michelle focus on traditional ideas of physicality, Cal adds the adjective “subtle,” which seems to both acknowledge the liberating notion of activism, online or otherwise.

User Participation in a Social Media–Based Public Pedagogy

Cal’s vigorous participation obviously makes him a highly engaged digital citizen, but whether or not his efforts are effective is up for debate. Too strict a focus on participation levels can be a deceptive determinant; after all, it can be difficult to decide what counts as participation and what does not, or what should count and what should not. In “Users Like You? Theorizing Agency in User-Generated Content,” José van Dijck examines the agency inherent in user-generated content and contends that user participation is far more complicated than the simple categorization of what one produces or consumes. With users like Cal it is easy to see the ways they produce content—he purposefully seeks civic and/or political content to share with fellow citizens. And even PJ, Michelle, and Gabrielle’s more everyday participation, though less traditional, is still identifiable. But there are even less obvious ways to participate, ones that could still contribute to the democratization of information Cal mentions. Even someone who doesn’t believe him or herself to be a contributor can still be contributing on some level.

The experiences of Christina, another student activist in my study, offers a stark contrast with that of Cal. Christina is a 20-year-old Hispanic junior and member of Society of Women Engineers (SWE). She doesn’t trust the Internet and says she chooses not to contribute to social media spaces even though she belongs to Facebook. She refuses to have conversations in “such a public space,” relying instead on the Facebook’s private message function to communicate with friends. Christina calls it a “credibility thing,” and explains that:

I don’t think something is credible if it’s on Facebook. There are more credible places to debate. It’s hard to value information online. It’s the little things, like when people type informally, when they type a ‘u’ instead of ‘you.’ It decreases their credibility. I mean, can’t you take the time?

Christina’s skepticism of the Internet leaves her in the position of “lurker” or “consumer.” Because she values credibility, Christina thinks that to be worthy of a public audience, one should be an expert on a subject. She doesn’t consider herself an expert on anything, so she refuses to post content and always questions the content others post: “People don’t have credit behind their names. They are just people, like you and me. I don’t like to post things in that sense.” This perspective is derived from both high school and college instructors who focused intently on the unreliability of Internet sources, Christina says, and did not focus at all on the positive attributes of the Internet. While learning to critically question content is certainly a valuable skill, one that seems to have taught Christina the important rhetorical concept of ethos, it appears to have also kept her from feeling comfortable participating, even casually, in social media-based information exchanges.

During interviews, Christina struggled to come up with any positive examples of how she used Facebook, but eventually came up with story about a Facebook event created to support victims of the earthquake in Haiti. As she describes it, newsfeeds showed various friends RSVPing to the event and awareness being raised. In this instance Facebook helped Haiti, Christina believed, but added “face-to-face efforts would have had more impact.” However in explaining how the face-to-face efforts would work she struggled to describe how they would work better than Facebook online tools. Due to her fear and distrust of online communities, Christina ultimately did not accept invitations to the Haiti event, or any others, nor did she donate money to Haiti in any manner, online or otherwise.

While Christina did not contribute in this particular case of online civic activism, her time-use diary shows that she does contribute in smaller, less concrete ways to the public pedagogy of Facebook. For example, her diary shows that she “likes” things on Facebook often in order to “encourage other people to also like them or so other people will become aware of [the content].” Here, it can be argued the simple act of liking a link or a status update ensures that the content will reappear in friend’s newsfeeds. Christina would consider herself exclusively a consumer in this case, and yet, the act of “liking” actually produces content in a similar fashion to retweeting. Therefore, even though Christina labels herself as merely a “lurker” or “consumer,” her participation, albeit small or “subtle” as Cal termed it, positively contributes to Facebook’s public pedagogy, thereby enacting some level of small-scale democratic practice. Indeed, since public pedagogy hinges on both teaching and learning, it can be argued that the size of contribution isn’t what matters. After all, lurkers can learn a lot, reinforcing the fact that someone like Christina could actually be considered a participant even if she’s not actually producing very much content.

Van Dijck puts forth a very similar notion, arguing that by no means does merely using networked technologies make someone an active participant (“Users Like You” 44). After all, when considering a social media-based public pedagogy, trying to determine what counts as participation may actually turn into a contradictory and unproductive event. For example, van Dijck cites a Guardian article from 2006 that offers an emerging rule of thumb suggesting that “if you get a group of 100 people online then one will create content, ten will ‘inter-act’ with it (commenting or offering improvements) and the other 89 will just view it” (44). In terms of public pedagogy, not only does this statistic privilege a measurable, product-oriented view of participation by failing to account for the unseen acts of learning that might have occurred in the 89 viewers, but it also shows the contradictory understanding of the concept itself. In her Handbook on Public Pedagogy, Sandlin asserts that, generally speaking, teaching is not acknowledged in the same way that learning is within public pedagogies. In the above conceptualization of Internet passivity, the creation of content is equated with teaching—the obviously more privileged act—whereas the viewing is considered learning, a subtle and therefore discredited act. However, if we switch our perspective to focus on pedagogical exchanges with regard to their ability to enact measureable change (as Gabrielle and Michelle do) we would discount the content creation unless we could actually see its effects on others, while we might privilege the learning because when we learn something from someone else’s content we may witness a change in our own knowledge base. Boyd agrees that the lack of measurement in social media content sharing can be confusing, as she argues, “offline, you know if a door has been slammed in your face; online, it is impossible to determine the response that the invisible audience is having to your message” (“Can Social Networks Enable”). In this sense, the majority of participants who doubted their contributions as teaching could more easily acknowledge the learning that took place for them. Either way we look at it, trying to measure what actually counts as participation leaves one confused and perhaps doubting that anything counts (as Gladwell might argue), or alternatively, deciding that everything counts. That being said, regardless of the measurability of such content production or participation, research shows that a citizen’s general social media activity can “ascribe a heightened level of engagement with society, enhancing cultural citizenship” (van Dijck 44), precisely due to the democratization of information that social media allows.

Affinity Spaces and the Democratization of Information

The democratization of information is a fundamental element of public pedagogy, one that makes social media sites such ripe learning platforms for enhancing civic involvement, especially if we look at them as “affinity spaces,” or what Hayes and Gee call “places where people go to get and give resources” (188). Whether or not the student activists in my study understood the concept of public pedagogy or agreed with the civic value of social media or the definition of civic participation, all of them believe that digital writing environments allow for conversations and connections, or resource exchanges, that are often impossible face-to-face. PJ, the Nigerian senior, argues social media evens “the playing field.” He believes that:

The biggest thing about life is communication. And how we communicate with people and how we accept communication is how we are able move forward. When you’re not able to communicate with people because of language barriers, or opinions or values, it kind blocks you from knowing more. You can learn something from someone who is not from the same background as you. Understanding their values and background can make your life better. You can take it or leave it, but you want to understand it.

PJ’s view speaks to the essential attributes of what an affinity space offers—an informal location, either physical or virtual, where individuals can come together to communicate with and learn from one another based on shared interests (Hayes and Gee 188). Hayes and Gee argue that “allow[ing] people to relate to each other primarily in terms of common interests, endeavors, goals, or practices, not primarily in terms of race, gender, age, disability, or social class” gives civic-minded individuals many new tools with which to converse and engage. In terms of participation, affinity spaces offer various and multiple ways to engage. Both beginners and masters are accommodated by the same space, as are vigorous and peripheral users (Hayes and Gee 188). In essence, anyone can be teacher or student. Such inclusiveness allows for the acknowledgement of all voices and returns to the fundamental democratic principle of vox populi, or voice of the people (Hayes and Gee 188; Hauser 3).

The affinity spaces of social media-based public pedagogy provide opportunities for the type of social knowledge making and remaking that James Berlin’s transactional rhetoric are based upon and which Kenneth Bruffee sought to manufacture via collaborative learning. In both of these movements, knowledge or truth is co-created through social interactivity; it is dependent upon conversation and collaboration with others. Likewise, as some of the success of social media lies in its ability to embrace the power of the Web to harness collective intelligence, it is dependent upon user-generated content and user participation in this co-creation of knowledge. These environments therefore combat some of the critiques that Bruffee received with regard to collaborative learning, namely that it could lead to consensus via peer pressure. Furthermore, one of the main advantages these spaces offer is the opportunity for abnormal discourse. Abnormal discourse promotes conversation that does not follow consenting paradigms as normal discourse does, but rather holds the potential for new or “revolutionary” thought and action—the kind needed to enact social change and resist hegemonic order (Bruffee; Gee). It is worth noting that abnormal discourse hinges on the intersection of varied and often-contradictory perspectives, the converse of what Gladwell’s strongly tied activists share.

A recent Pew Research Center study entitled “Internet and American Life” found that social media users were more likely to have higher levels of what they call “perspective talking,” defined as the ability to consider and engage multiple perspectives as well as the openness to consider new points of view (Hampton et al. “Social Networking Sites and Our Lives”). Moreover, social media users were more likely to learn more about the subject at hand as they engage in this “perspective talking,” for online debates hold the potential to incite deeper levels of thought and information exchange due to the fact that they don’t have to happen in real time. In our interview, Cal pointed out that one of the benefits of online debate is being able to see a response—and further educate himself on the topic —before responding back. Accordingly, the participatory nature of a social media-based public pedagogy, with its emphasis on reciprocity rather than sacrifice, allows the inherent rhetorical character of civic society to create arenas where “strangers encounter difference, learn of the other's interests, develop understanding of where there are common goals, and where they may develop the levels of trust necessary for them to function in a world of mutual dependence” (Hauser and Benot-Barne 271). The opportunity for these kinds of encounters is ripe among weakly-tied individuals, whereas strong bonds often exist upon commonality, thereby minimizing difference.

While the subtle actions of someone, like Christina, “liking” things on Facebook may not have the effect (or intent) that Cal’s social media activities do, they are still an essential part of the subtle public pedagogy process, as these affinity spaces rely on both enthusiasts like Cal and skeptics like Christina to fill out the spectrum of participants from amateur information producers to professional media consumers, blurring lines between teacher and student. And while Cal’s vigorous participation is certainly part of what makes him an effective digital citizen, I argue his self-awareness of how his participation might affect his world is actually the more important part of the equation.

For instance, if skeptics, like Christina, recognized the civic potential of their actions in affinity spaces, her subtle participation might quickly turn into something more fruitful and fulfilling. When one is aware of what can count as participation, it follows that such a person might choose to participate more often and more intently (Ma). Social media relies on the user or it fails; Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Reddit, and other social media sites are only as powerful as the user makes them. For digital citizenship and activism to hold real value, users need to be integral rather than accidental. They need to recognize and value their activity.

Gladwell argues that “just because innovations in communications technology happen does not mean that they matter.” Put another way, Gladwell argues that in order for an innovation to make a real difference, it has to “solve a problem that was actually a problem in the first place” (“From Innovation to Revolution”). However, social media is contributing to solutions by encouraging civic engagement, educating citizens, and democratizing information. The democratization of information inherent in social media-based public pedagogies is a civic act in and of itself—both in terms of the teaching and the learning it offers—and in the unparalleled opportunities it offers for civic activism and perhaps even revolution. In 2006, years before the activist agenda of social media became a hot topic, a group of graduate students and faculty at Michigan State University interested in digital writing practices conjectured, “the tools themselves are revolutionary, but the more important, more significant revolution is the possibilities for connection and communication—framed by convergence and interactivity” (digirhet.org). In other words, people must connect to create change and meet to effect progress. And social media—more than any means of communication that has come before—allows us to make these connections in spades. Even if the digital exchanges that occur in these spaces are not revolutionary in size, it is important to remember that all progress starts with small change.

Notes

[1] “Net Generation” is a term used to describe those born between 1977-1997, many of whom have grown up with digital technology as a central part of their communicative life. This group comprises roughly 27 percent of the U.S. population (Grown Up 16).

[2] Time-use diaries, often used by social scientists, are a qualitative technique “wherein research participants keep detailed records of their time usage relative to a specific activity” (Hart-Davidson 153-4).

[3] Several months after my interview with Cal, the primarily social aspect of Wikileaks—the wiki—was shut down, thereby preventing further posting (Gilson, “Wikileaks Gets a Facelift”). Users may still download information, however.

Works Cited

Alan. “Re: Power of the Personal Message.” The New York Times. 30 Sept. 2010. Web. 5 Oct. 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2010/09/29/can-twitter-lead-people-to-the-streets/reaching-and-persuading-the-masses>.

Baurelin, Mark. The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future (Or, Don't Trust Anyone Under 30). New York: Tarcher, 2008. Print.

B Bennett, Lance. “Changing Citizenship in the Digital Age.” Civic Life Online. Ed. Lance Bennett. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008. Print.

________. “Digital Natives as Self-Actualizing Citizens.” Rebooting America: Ideas for Redesigning America in the Internet Age. Eds. Allison Fine, Micah L. Sifry, Andrew Rasiej, and Josh Levy. New York: Personal Democracy Press, 2008, 225-230. Print.

Berlin, James. Rhetorics, Poetics, and Cultures. Urbana, IL: NCTE, 1996. Print.

boyd, danah. “Sociable Technology and Democracy.” Extreme Democracy. Eds. Jon Lebkowsky and Mitch Ratcliffe. Lulu: 2005. Print.

________. “Why Youth (Heart) Social Network Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life.” Youth, Identity, and Digital Media. Ed. David Buckingham. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007. 119-142. Print.

________. “Can Social Network Sites Enable Political Action?” Rebooting America . Eds. Allison Fine, Micah Sifry, Andrew Rasiej and Josh Levy. New York: Personal Democracy Press, 2008. 112-116. Print.

boyd, danah, Scott Golder, and Gilad Lotan. “Tweet, Tweet, Retweet: Conversational Aspects of Retweeting on Twitter.” Proceedings of HICSS-43 (2010): 1-10.

Bruffee, Kenneth. “Collaborative Learning and the ‘Conversation of Mankind’.” College English 46.7 (1984) 635-652. Print.

Cal. Personal interview. 15 February 2010.

Christina. Personal interview. 17 February 2010.

DigiRhet.org. “Teaching Digital Rhetoric: Community, Critical Engagement, and Application.” Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 6.2 (2006): 231-59.

Ehrlich, Thomas. Civic Responsibility and Higher Education. Westport, CT: American Council on Education/Oryx Press, 2000. Print.

Gabrielle. Personal Interview. 5 March 2010.

Gilson, Dave. “WikiLeaks Gets A Facelift.” Mother Jones. 19 May 2010. Web. 24 March 2011.

Giroux, Henry A. “Beyond Neoliberal Common Sense: Cultural Politics and Public Pedagogy in Dark Times.” Journal of Advanced Composition 27.1 (2007) 11-61. Print.

________. “Living in the Age of Imposed Amnesia: The Eclipse of Democratic Formative Culture.” Truthout. 16 November 2010. Web. 17 January 2011.

________. “The Crisis of Public Values in the Age of the New Media.” Critical Studies in Media Communication. 28.1 (March 2011). 8-29. Print.

Gladwell, Malcolm. “Small Change.” The New Yorker. 4 October 2010. Web. 25 October 2010.

________. “Does Egypt Need Twitter?” The New Yorker. 2 February 2011. Web. 3 March 2011.

________ and Clay Shirky. “From Innovation to Revolution: Do Social Media Make Protests Possible?” Foreign Affairs. April 2011. Web. 19 July 2011.

Grabill, Jeffrey T., and Troy Hicks. “Multiliteracies Meet Methods: The Case for Digital Writing in English Education.”English Education 37 (2005): 301– 11. Print.

Hampton, Keith et al. “Social Networking Sites and Our Lives.” Pew Internet and American Life Project. Pew Research Center, 11 July 2011. Web. 21 Aug. 2011.

Hart-Davidson, William. “Studying the Mediated Action of Composing with Time-use Diaries.” Digital Writing Research: Technologies, Methodologies, and Ethical Issues. Eds. Heidi McKee and Danielle Nicole DeVoss. Cresskill NJ: Hampton Press, 2007. Print.

Hauser, Gerard A., and Benot-Barne, Chantal. “Reflections on Rhetoric, Deliberative Democracy, Civil Society, and Trust.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 5 (2002): 261-75. Print.

______ and Grim, Amy. Rhetorical Democracy: Discursive Practices of Civic Engagement. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2003. Print.

Hayes, Elizabeth and James Paul Gee. “Public Pedagogy through Video Games.” Public Pedagogy: Education and Learning Beyond Schooling. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Jenkins, Henry and David Thorburn. Democracy and New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003. Print.

Kwak, Haewoon, et al. “What is Twitter, a social network or a news media?” Proceedings of the 19th international conference on World wide web. ACM, 2010.

Lenhart, Amanda et al. “Social Media and Young Adults.” Pew Internet and American Life Project. Pew Research Center, 3 Feb. 2010. Web. 3 Feb. 2010.

Ma, Lin. “Slacktivism: Can Social Media Actually Cause Social Change?” The Big

Chair. Fairfax Digital, 01 Oct. 2009. Web. 03 July 2010.

Michelle. Personal interview.

PJ. Personal interview. 2 April 2010.

Pegrum, Mark. From Blogs to Bombs. Crawley, Western Australia: UWA Publishing, 2009.

Sandlin, Jennifer A. Handbook of Public Pedagogy: Education and Learning Beyond Schooling. New York: Routledge, 2010.

WIDE Research Center Collective. “Why Teach Digital Writing?” Kairos: Rhetoric, Technology, Pedagogy 10.1 (2005). 20 Mar. 2007. <http://english.ttu.edu/kairos/10.1/binder2.html?coverweb/wide/index.html>.

WikiLeaks .Web. 9 November 1010 <http://wikileaks.org/About.html>.

Tapscott, Don. Growing Up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998. Print.

___________. Grown Up Digital: How the Net Generation is Changing Your World. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Print.

van Dijck, José. “Users Like You? Theorizing Agency in User-Generated Content.” Media Culture & Society 31 (1): 41-48 (2009). Print.