- Introduction to the Issue

- Nietzsche was a DJ

- DJ Spooky Interview

- Common Sounds

- inter.Virtual.Vitalism. views: Aural Encounters

- How Music Speaks: In the Background, In the Remix, In the City

- Writing Without Sound: Language Politics in Closed Captioning

- 'Digimortal': Sound in a World of Posthumanity

- Thinking Across the Neck: Playing Slide with Fret/work Blues

- An Autoethnography of Sound: Local Music Culture in Colorado

- Inquiry as Telos

- A New Composition, a 21st Century Pedagogy, and the Rhetoric of Music

- Remixing the Personal Narrative Essay: “The Hardest and the Best Thing I Have Ever Done”

- Auralacy: From Plato to Podcasting and Back, Again

- Digital Lyrical

- Contributors' Notes

Thinking Across the Neck: Playing Slide with Fret/work Blues

Cynthia Haynes

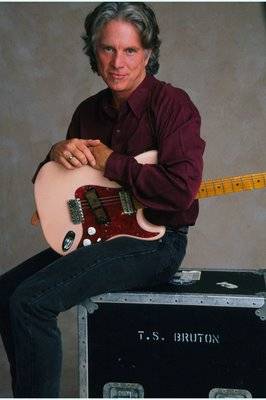

When I think of Stephen Bruton, who died in 2009, I picture this scrappy good-lookin’ kid just back from Woodstock, cowboy hat tilted, stopping for a moment on the threshold to adjust his eyes to the dark interior of the HOP in Ft. Worth that summer of 1970 when I turned 18. I was sittin’ at a table with his brother, Sumpter, and another friend I’ll just call Vern. Stephen rushed over, tipped his hat to me briefly, pulled up a chair, turned it backwards and sat down in one swift movement. Vern says, “it’s about damned time you got back home, kid, ‘cuz ‘Little Whisper and the Rumors’ ain’t nothing without the Little Whisper.” Stephen gave him that Stephen smile and said: “Kristofferson’s offerin’ me lead guitar, man, and that’s gonna put a hurt on the Rumors if I leave.” So that night he played, and would do so over the next decade every time he returned home from his road trips playing with Kris, Bonnie Raitt, T-Bone Burnett, you name it. One time, as I watched him setting up at the HOP, I noticed that he had had his nomadic life emblazoned on the back of his cowboy boots. On the left boot in red rhinestone stitching it said “Adios” and on the right boot, it said “Mother” —Adios Mother. Strange that when I heard he had passed away, my first thought was to wonder where those boots are now; and the second thought was not a thought at all...it was a ‘feeling image’ of Stephen playing guitar, a shiny silver Dobro guitar the neck of which he caressed with a shiny silver slide while singing “Sittin’ on top a thu world.”

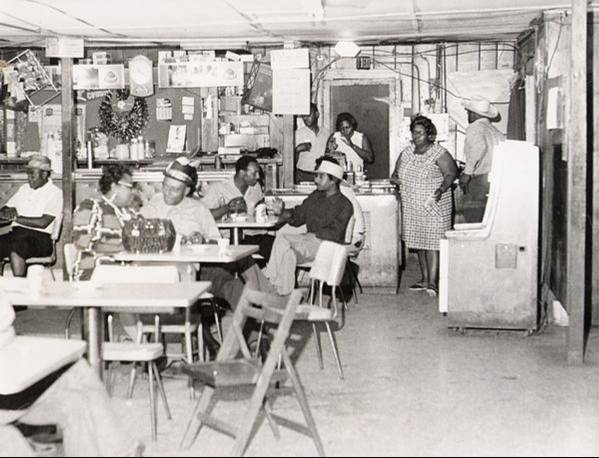

Blue Bird Night Club

As I started “thinking across the neck” to conceive this paper, I had not then heard the rumor of his illness. I hadn’t seen him in years. That he died of complications from throat cancer is tough, now, given what I wanted to think through and across the relationship of slide guitar to composition. Mostly what I think is that it’s been impossible to think about this topic…it doesn’t lend itself to thinking at all. And that surprised me. How NOT to think about something puts me on unfamiliar academic ground. So, I decided to just write from where his fretwork took me, and settled on the task of taking the pathos and mixin’ it up with a little of the juke joint and roadhouse blues I have loved for the past four decades.

Stephen Bruton

It's the Voice

In his book The Devil’s Music, Giles Oakley finds that: “Many blues singers consider the guitar a second voice” (55). According to “Jelly Jaw” Short, Delta bluesman Charley Patton “used to play the guitar and he’d make the guitar say ‘Lord have mercy, pray, brother, pray, save poor me’” (55). Oakley adds that “Patton’s blues speak with several voices simultaneously. In the words of his songs,” but also in the “damped down, ‘dirty’ toned, monotonously repeated bass figures giving a heavy emotional undertow, lightened by the sensuously rising and sliding notes, driving and swinging with the joy of release” (55). “When your way gets dark, baby, turn your lights up high, /[spoken] What’s the matter with ‘em? /Where you see my man, Lordy, he come casin’ by… /Trouble at home, baby” (55). These lyrics inspired Jeffrey Carroll’s book, When Your Way Gets Dark: A Rhetoric of the Blues. But here’s the thing, and to Carroll’s credit he also sees this point. We don’t know the first thing about voice. At least not those of us in the business of playing the intellectual broken record of writing theory on these overpriced rented gramaphones we plug into our laptops. We’re just hoping, still, that the vinyl flat disk will somehow plug us into “feeling” the blues. Carroll is up front about this problem. Let’s hear how he wrestles with it: “The structural principles of the blues critic are in no way different from the critic at large. His rhetoric, too, is not different . . .[it’s] the intellectual employing the sorcery of a Western rhetoric in order to save, protect, or champion the threatened texts of others . . . . [And yet] He or she believes in the marginalized text—its soul, its make, its value to the center, to the margin, to the world. He or she may even ‘like the text, though that is certainly giving a part of the game away . . . . And I, too, champion the blues, love it, and grieve for it—yet these admissions are beside the point. In rhetorical terms, my argument has become too personal, stuck in my own feelings rather than attempting to identify or validate those of the audience, of which I am only one member . . . . If the blues is dying, are these thousands of voices a linguistic hospice, or is something else at work here, a transgressive industry of rhetoric designed by its users to provide a cultural Other, the apparition of darkness that America has always needed and nurtured in its own forests, alleys, and music halls?” (9-10).

The blues is dying, but my purpose in speaking to you today about it is not because I aim to play the blues critic, or to disinherit my “whiteness” to talk about what is clearly and unambiguously an accumulative historical slumming whenever I go back in time to re-live, and re-capture, the voices that pulled me through my young adult angst-ridden decades. NO. The problem is that I am dying. But please do not hear this as a truth statement. To say I am dying is to put voice in its place. Or at least to try to—for voice sits in my body precisely at the most vulnerable place possible—my neck. One could say that this puts you, my audience, in the role of the “neck” of the guitar, and my “thinking across the neck,” if we can call it that, is an attempt to “worry” the fret—or take the fret from its noun to its verbal form—to fret. This is the anxiety Foucault suggests is at the heart of the problem of the “order of discourse,” namely, that we are anxious because we are all faced with “a transitory existence, destined to oblivion” (216) at a time not of our own choosing. This is the fretted voice I hear, and crave, when I hear the blues, and in particular when I hear the blues guitarist using a slide to make his guitar say, more or less, “I am dying.” The slide takes hold of the voice and de-strangulates the cutthroat tones, the swift decapitations of delicate notes prolonging life with every mourn/full extension.

I kind of like that sentence, but I can already feel my thinking trying to take off the slide. It’s starting to pull the feeling away from the dying, to order the dying to stop. And it makes me want to whisper the suggestion I’m about to make: that teaching writing has been too much about ordering our students’ dying to stop, assigning it to stop. Just write an argument against dying, we say. Support your claim upon life with evidence that you are not dying. But it’s their dying we’re mucking around with. It would be better to just give them a slide and assign them to fret. Muddy Waters once told his side guitarist, Bob Margolin, “‘When Little Walter quit me in ‘52, it was like someone cutting off my oxygen -- I didn’t know how I was going to play without him. But soon I realized I had to put the slide back on my finger and go out and be Muddy Waters.’” And Bob says that “near the end of [Muddy’s] life, he was trying to do that again.”

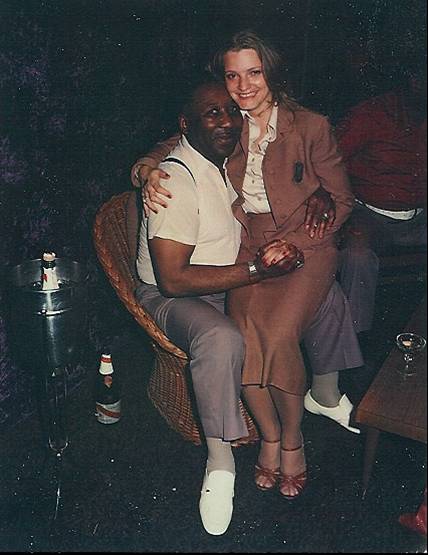

Muddy Waters and Cynthia Haynes

It’s the Connection

But setting aside the livin’ and dyin’ for a moment, which feels wrong somehow, I want to follow for a bit what happens when one slips the slide on. One instructor, Dirk Hageman, explains the slide technique as follows: “When playing slide, the two most important words to remember are tension and anticipation. When a guitar is played in ‘normal’ fashion, the notes are struck with a sharp attack and then the note gradually decays. With a slide, the attack becomes much longer, producing an almost horn-like tone. What makes the sound of slide guitar so poignant is that the notes are ‘squeezed’ out of the guitar, rather than ‘struck’ out of the guitar.”

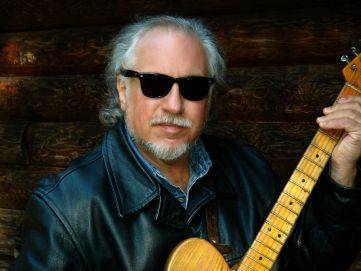

Bob Margolin

I wanted to talk to Stephen about this, but by then it was too late. So, I contacted another guitarist friend, Bob Margolin, who I had not seen since meeting him at Antone’s in Austin in 1976 on Muddy’s 63rd birthday. Turns out he lives not far from us in the Carolinas, and we went to one of his gigs in Charlotte to re-connect. Afterward we had the following exchange by email:

Me: What I want to do is focus on the ‘slide’ aspect of your playing. I noticed that when you use a slide, you become more aggressive with the guitar...that is, you do what I would call ‘worrying’ the neck a bit hard, even to the point where you seem to be ‘willing’ it to say something different to you...to us. So, my question is...does this tendency depend on the song you’re involved in at the moment? Or do the lyrics ‘call’ for this type of treatment of the instrument? Is it, in other words, a response to WHAT you are singing, or a way to heighten and convey best what you are singing?

Bob: Actually, that's just physics. Without slide, I have 4 fingers on the neck to hit notes, with the slide, I use mostly the little pipe on my finger. I know it looks more dramatic, and I tend to use more vibrato with the slide. I rarely think about things like that, just do them, so it's interesting to know how you see it and what you surmise.

Me: I realize that most slides originated as homemade bottlenecks (or something made of steel), and that there are lots of improvised devices used as slides. Can you tell me what various devices you have used over the years yourself (and why), what unusual slides you have seen used by others (and who used them)?

Bob: I'm less picky about slides than others -- whatever works. Muddy used a short slide on the tip of his pinky, could only hit 3 strings at a time. I prefer about a 3 inch pipe that fits snug but not tight, on my pinky. I can hit more strings if I want to, in open tuning. When I first tried to play slide in the late '60s, I took a Coricidan glass bottle. I believe Duane Allman did that too. Coricidan bottles are plastic now, but you can buy the old-style bottles. Glass sounds smoother than steel, but it's a matter of choice, and I don't have a strong preference. I carry steel because it's less likely to break. Sometimes at home, when recording, I'll use glass if that's what I grab first.

Me: How did Muddy’s use of slide influence your playing slide?

Bob: I think that being able to slide up or down to a note and use the pitches between the notes to bend them is more vocal-sounding than just hitting one note of a scale, as on a piano or guitar played without expression. And the slide is certainly more expressive. In Muddy's song "Louisiana Blues," there's one note he hits where he slides down, as if disappointed, and it's the Bluest note I've ever heard on a guitar.

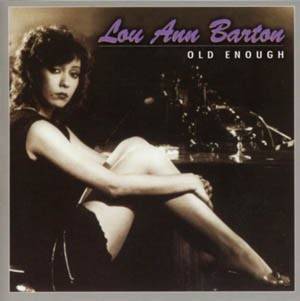

Lou Ann Barton

I was particularly affected by meeting and hearing Muddy Waters in the mid-70s, but my roommate during those years, Lou Ann Barton, had also introduced me to bluesmen long gone: Elmore James, Robert Johnson, Jimmy Reed. We’d play their records sittin’ in our tiny living room on the east side of Ft. Worth, and the old man livin’ on the other side of our $50 a month duplex would bang the walls when we’d start up the record player. He didn’t much like our carryin’ on. But we were ‘getting’ down in some connection.’ In the 30s, when Delta bluesman, Robert Johnson, played guitar, the multiple registers of wailing and moaning echoed his vocal craft. In “Terraplane Blues,” it is often hard to tell the difference between the instrument and the story of one man’s worry about another man ‘driving his Terraplane’ while he’s been gone, the car a metaphor for a his ‘woman,’ his need to ‘get down in her connection and keep on tanglin’ in her wires’ a fairly unsubtle reference to the most basic form of connectin’. Johnson was not the first to use a ‘slide’ to hitch the sounds to the language, but he is arguably the most classic example of how playing slide “causes you to think across the neck, not up and down it” according to Matt Desenberg.

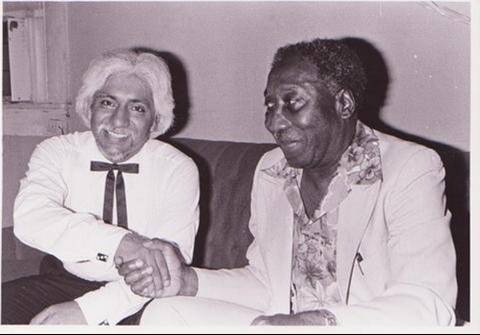

Freddie Cisneros and Muddy Waters

But connection as intimacy has a nefarious flip-side. While Hawaiian guitarists of the early 1900s used steel bars to play slide, Delta blues guitarists resorted to whatever they had at hand, or in their pocket, such as small knives—which gives a whole new meaning to ‘thinking across the neck.’ Most guitarists, however, used bottleneck glass. I’ve also seen guitarists grab whatever was handy—a salt shaker, the back of a chair. But one Ft. Worth friend, Freddie Cisneros, would bring a small trunk on stage from which he would pluck a plastic fish, or a rubber chicken, to play slide—hence he and his band were dubbed, eventually, Little Junior One Hand and the Blasting Caps. Stephen Bruton sometimes used a spark plug for a slide, and I imagine he was channeling Johnson’s “Terraplane Blues”, it is some kinda “hoo-well [to] keep on tangling with your wires/And when I mash down your little starter/then your spark plug will give me a fire.”

Stephen Bruton and T-Bone Burnett

It's the Blues

Some of you may have seen the film Crazy Hearts by now. I haven’t yet, but when I do, it will be hard to see the dedication to Stephen Bruton up on the screen, to know that he died two weeks after the film wrapped at the home of his Texas childhood buddy, T-Bone Burnett. Apparently Jeff Bridges learned a thing or two from Stephen as he prepared for the part. Perhaps Stephen even taught Jeff how to slide into the other side, how to take an epiphany, slip it on, and play himself into his “destined oblivion at a time not of his own choosing.”

Stephen Bruton Interview

Video:

Stephen Bruton: http://www.epiphanychannel.com/people/stephen-bruton/

Stephen Bruton - Getting Over You

Video:

Bruton's "Getting Over You": http://www.mydamnchannel.com/channel.aspx?episode=1496

Works Cited

Bruton, Stephen. “Getting Over You.” MyDamnChannel.com (http://www.mydamnchannel.com/channel.aspx?episode=1496) 9 Feb 2011.

Carroll, Jeffrey. When Your Way Gets Dark. A Rhetoric of the Blues. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2005.

Desenberg, Matt. “The Benefits of Slide Guitar.” GuitarNoise.com (http://www.guitarnoise.com/lesson/benefits-of-slide-guitar/) 9 Feb 2011.

Epiphany Channel. Stephen Bruton Interview by Elise Ballard. (http://www.epiphanychannel.com/people/stephen-bruton/). 9 Feb 2011.

Foucault, Michel. “The Discourse on Language.” The Archeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith. NY: Pantheon, 1972. 215-237.

Hageman, Dirk. “Learning Slide Guitar.” BluesLessons.net. (http://www.blueslessons.net/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=62&Itemid=41) 9 Feb 2011.

Margolin, Bob. Personal email. 17 September 2009.

Oakley, Giles. The Devil’s Music: A History of the Blues. London: Da Capo Press, 1997.