- Introduction to the Issue

- Whose Literacy Is It Anyway? Examining a First-Year Approach to Gaming Across Curricula

- Computer Games Across the Curriculum: A Critical Review of an Emerging Techno-Pedagogy

- What Games Have to Teach Us About Teaching and Learning: Game Design as a Model for Course and Curricular Development

- Four Ways to Teach with Video Games

- Life in Morrowind: Identity, Video Games, and First-Year Composition

- Stings and Scalpels: Emotional Rhetorics Meet Videogame Aesthetics

- The Avatar that therefore I Am (Following)

- Machinima-to-Learn: From Salvation to Intervention

- Procedural Rhetorics / Rhetoric's Procedures: Rhetorical Peaks and What It Means to Win the Game

- Gone Gitmo: An Interview with Co-Creators Nonny de la Peña and Peggy Weil

- Serious Games Interactive Interview

- Contributors' Notes

Procedural Rhetorics - Rhetoric's Procedures: Rhetorical Peaks and What It Means to Win the Game

Matt King

In Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (2007), Ian Bogost describes the connections between rhetoric and procedurality, showing how processes, logics, and systems of rules constitute a form of persuasion and expression. He calls this persuasive and expressive mode “procedural rhetoric, the art of persuasion through rule-based representations and interactions rather than the spoken word, writing, images, or moving pictures” (ix). For Bogost, “[p]rocedural rhetorics afford a new and promising way to make claims about how things work” (29), about the processes, rules, and logics that structure individual attitudes and behavior as well as social and cultural systems and institutions. Bogost associates this notion of procedurality with such longstanding institutions and cultural conventions as courts and laws as well as its more recent instantiation in computer programming, but he ultimately wants to approach the concept generally: “Procedurality refers to a way of creating, explaining, or understanding processes” (2-3). Moreover, “processes define the way things work: the methods, techniques, and logics that drive the operation of systems, from mechanical systems like engines to organizational systems like high schools to conceptual systems like religious faith” (3). Procedurality thus seems to exist all around us, structuring our interactions with material objects, our social interactions and institutions, and even our minds. Procedural rhetorics in turn make arguments about these systems and the processes that structure them.

Videogames serve as particularly helpful and rich examples of procedural rhetoric to the extent that they embody processes and rely upon players to enact them (Bogost 44, 45). By embodying certain processes and not others, by structuring a playing experience around particular rules and logics, videogames make claims about the world and how it works – or how it does not work, or how it should work. Moreover, these claims only achieve their full expression through user input. Bogost describes the player’s role in the execution of a videogame’s logic with reference to the enthymeme – “the technique in which a proposition in a syllogism is omitted” and where “the listener…is expected to fill in the missing proposition and complete the claim” (43) – with players providing the missing assumption through their performance in the game. Of course, any number of texts make claims about how the world works by describing or evoking certain processes or systems, but very few modes of textuality make these claims through processes themselves, as videogames do.[1] To take an example that Bogost considers, Molleindustria’s McDonald’s Video Game makes arguments about the negative impact of certain food industry practices in their disregard of animal rights, health standards, and environmental concerns. Many books, articles, films, and other sorts of texts have made similar arguments, but only the game makes its claims through the processes it requires players to enact. An article can describe the way beef gets from the field to your Happy Meal, but the game makes the player slaughter the virtual cow herself and serve tainted meat to customers in order to make profits.

Bogost’s account of procedural rhetoric, as well as his focus on videogames, invites a range of new practices for rhetoricians, from articulating and utilizing new modes of (procedural) rhetorical analysis to exploring the possibilities that procedural rhetorics and videogames make available for new approaches to argumentation and other forms of expression.[2] Here, I would like to examine and expand on the connections that Bogost makes between rhetoric and videogames to question the extent to which we can think of rhetoric itself as procedural. As a developer of Rhetorical Peaks – a videogame for rhetoric and writing classes created by the Digital Writing and Research Lab at the University of Texas at Austin – I have questioned the extent to which we can think of rhetoric as procedural, as something that could be defined by rules and processes. This concern in turn calls into question the ability of a videogame, that is, a tool that describes phenomena procedurally, to teach rhetoric. For Bogost, “[w]hen we create videogames, we are making claims about…processes, which ones we celebrate, which ones we ignore, which ones we want to question,” and “[w]hen we play these games, we interrogate those claims, we consider them, incorporate them into our lives, and carry them forward into our future experiences” (339). From this perspective, all game design and game play is inherently rhetorical; a game’s processes and rules embody modes of persuasion and expression, and we can read and analyze them as such. But what if we switch the emphasis: to what extent is rhetoric procedural? In other words, could any specific set of processes – and thus, any videogame – describe what it means to do rhetoric? The quick answer seems to be that rhetoric is many things, a collection of teaching, reading, writing, and theorizing practices, each with their own processes. We could thus imagine any number of videogames dedicated to exploring these various processes and making arguments about how rhetoric works in different situations. But something about rhetoric eludes rules and resists any sense of our ever having “won the game.” After all, what would it mean to win the game of rhetoric?

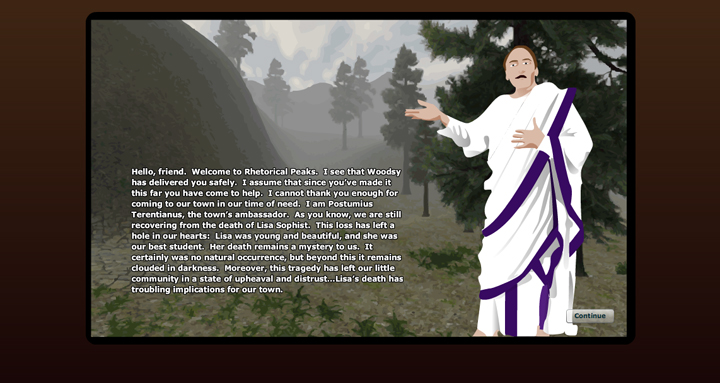

Rhetorical Peaks Title Shot, Flash version.

The Rhetorical Peaks project encountered the question of rhetoric’s procedures in its early development. Created as a module in BioWare’s Neverwinter Nights using the Aurora toolset, the original prototype of the game confronted the player with a mysterious death in the fictional town of Rhetorical Peaks. The player was responsible for accumulating evidence that could be used to make an argument about the cause of death and could do so by completing three quests, each related to one of the classical rhetorical appeals (logos, ethos, and pathos). Embedded in each of these quests was a procedural rhetoric, a set of processes that made an implicit claim about how each particular appeal works. So, to gather information from Woodsy the raven in the Woods of Ethos, the player had to demonstrate her credibility by wearing an outfit that suggested a sensitivity to environmental concerns. In the story, some citizens of Rhetorical Peaks had done great damage to the Woods of Ethos, and Woodsy needed to be convinced that the player was trustworthy. This particular quest encouraged students to reflect on the importance of establishing credibility in a rhetorical exchange, but the procedural rhetoric underlying the quest failed to do justice to the complexity of the concept of ethos. The processes involved in the successful completion of the quest – find the wardrobe with a collection of different outfits, wear the outfit most appropriate for meeting with a friend of the forest – suggested that ethos could be understood as the practice of wearing clothes that reflect the values of your audience. On one procedural level, the Rhetorical Peaks prototype made an important point: successfully navigating a rhetorical situation requires the ability to appeal to an audience in various ways; on the other hand, the game did not offer a rich understanding of the processes underlying particular appeals. After all, not all environmentally conscious ravens are going to trust you just because your clothes are made of organic cotton. Some might trust you less for faking it.

It is worth pointing out here that a procedural rhetoric designed to make claims about the way rhetoric itself works would not need to account for all of the processes that describe what it means to do rhetoric. For Bogost, “meaning in videogames is constructed not through a re-creation of the world, but through selectively modeling appropriate elements of that world” (46). In other words, “[p]rocedural representation models only some subset of a source system, in order to draw attention to that portion as the subject of the representation” (46). By directing our attention toward particular processes, procedural rhetorics advance “a claim about how part of the system it represents does, should, or could function” (36). To recall the earlier example, the McDonald’s Video Game does not incorporate all of the processes involved in raising livestock, working at a fast-food restaurant, and running corporate board meetings; instead, it highlights those processes that most clearly present some of the negative aspects of the fast-food industry, suggesting that these procedures capture the essence of companies like McDonald’s. A rhetoric videogame could thus highlight particular processes to represent how rhetoric does, should, or could function, but this possibility once again evokes the question of rhetoric’s procedures.

There are at least two concerns that complicate the question of which procedures describe what it means to do rhetoric.[3] One has to do with rhetoric’s traditional emphasis on context and kairos, the way that “contexts shift in time” (Crowley and Stancliff 84), an emphasis suggesting that the success of any gesture toward persuasion and expression can only be determined contextually and with reference to a particular audience and situation. The second concern has to do with the instability of language and its inability to fully capture its referent. Kenneth Burke gets at this concern when he notes how our vocabularies aim to be “faithful reflections of reality” but necessarily become “selections of reality” that also “function as a deflection of reality” (Grammar 59). Jacques Derrida’s notion of différance presents a more radical stance on the instability of language, describing language not as a simultaneous selection and deflection of reality but rather as something that refers only to itself, never escaping an endless chain of textuality to arrive at a stable referent. Perspectives such as Burke’s and Derrida’s that highlight the limitations of language have played a significant role in rhetorical discourses for several decades. Both of these concerns – the notion that meaning can only be determined contextually and that language is inherently unstable and/or unable to capture the real in its totality if at all – complicate the possibility of defining rhetoric’s “win state.” Given the limitations of language, this end point would not be “Truth” or a complete reflection of reality; it could be some notion of consensus, cooperation, or successful persuasion, but any instance of these would be situated, conditional, and contextual.

In this sense, rhetoric’s ends shift; to the extent that rhetoric’s ends stay the same, the means to those ends change. The game of rhetoric shifts around us, and no set of rules always guides us to success. If no particular set of processes results in winning the game of rhetoric, then it becomes difficult to imagine a procedural rhetoric that would do justice to rhetoric itself. It seems that we could define rhetoric according to a specific logic only if we simultaneously recognize that any such definition will be incomplete and will change in different contexts. In this sense, more than mastery of a particular set of processes, rhetoric requires the ability to negotiate and shift between processes. Put another way, responsible rhetoric necessarily involves a consideration of multiple procedures and logics, of the ways that different processes structure different attitudes, behaviors, and subjectivities. This is not simply a matter of knowing the processes underlying different forms of analysis and argumentation and performing them successfully. Instead, this notion of responsibility entails an ability and willingness to recognize and respect different logics and the inherent instability of the rhetorical situation.[4]

This perspective suggests another question: could a videogame capture this sense of instability and instill in a player a sense of responsibility to account for rhetoric’s shifting contexts? This question has shaped the development of Rhetorical Peaks; indeed, the game aspires to instill this sense of responsibility in players. In what follows, I will outline two influences – aspects of Kenneth Burke’s thought and Diane Davis’s understanding of “communitarian literacy” – that helped the Rhetorical Peaks project answer this question, and then show how these perspectives manifested themselves in subsequent developments of the game.[5] This is not an attempt to close the conversation; instead, I hope to illuminate some of the challenges that inform the attempt to design a procedural rhetoric that effectively expresses the concerns of rhetoric itself. In this sense, Rhetorical Peaks offers one response to the question of rhetoric’s procedures, and it invites others.

The Parlor, Unity version.

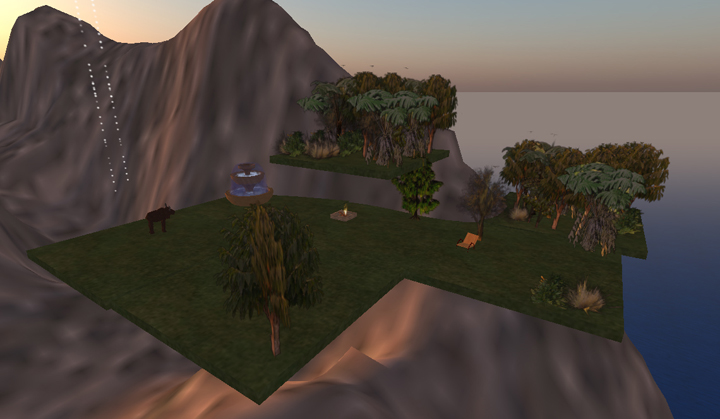

Woods outside Rhetorical Peaks, Unity version.

Amphitheater, Unity version.

Rhetoric’s Responsibilities

In Persuasive Games, Bogost credits Kenneth Burke with expanding rhetoric’s horizons beyond a focus on persuasion to a wider consideration of identification, such that “the basic function of rhetoric” becomes “the use of words by human agents to form attitudes or induce actions in other human agents” (qtd. in Bogost 20). As described by Bogost, “[w]e use symbolic systems, such as language, as a way to achieve this identification” (20). For Bogost, Burke’s larger concern with symbolic systems helps to widen the scope of rhetorical studies to include visual rhetoric, a subfield that proves quite relevant to videogames. As we have seen, Bogost’s interests ultimately lie beyond visual rhetoric in the realm of procedural rhetoric, and so after referring to Burke to open a discussion of visual rhetoric, Bogost quickly leaves him behind. The connection Bogost makes between Burke and visual rhetoric is a helpful one, but a more productive and relevant connection can be made between Burke and procedural rhetoric itself, specifically with reference to two of the terms mentioned above: attitude and identification. Although he does not use the term, Burke’s discussion of attitudes and identification suggests the notion of procedurality. As we will see below, attitudes – as well as a series of related concepts and terms such as orientations, motives, and rationalizations – act as frames that shape our experience in the world and the way we respond to that experience. In this sense, attitudes describe a logic of interaction that constrains the possibilities of our reactions to any particular situation. At the same time, a range of attitudes informs any specific situation or behavior, complicating this notion of procedurality. For Burke, the process of identification involves a similar logic of interaction, one negotiated through “speech, gesture, tonality, order, image, attitude, idea” (Rhetoric 55). Attitudes and identifications are both formed with reference to language and symbolic activity generally, and they can shift in different contexts and over time. A closer look at Burke will provide a more thorough understanding of these concepts and a perspective on rhetoric’s procedures.

In Permanence and Change (1935), Burke demonstrates how specific terms, vocabularies, and broader uses of language – what he will later call “terministic screens” – necessarily frame the world and shape our experiences in a particular way. His discussion begins with a consideration of the ways that we orient ourselves within the world and interpret it. Since “[t]he problems of existence do not have one fixed, unchanging character,…[t]hey are open to many interpretations” (10), and there is no orientation toward the world and the problems of existence that is not already an interpretation of them. Orientations can be understood as “a bundle of judgments as to how things were, how they are, and how they may be” (10). As bundles of judgments and collections of interpretations, orientations constrain possibilities of thought and behavior, limiting the range of perspectives we are capable of adopting in response to our experience. To the extent that they inflect behavior, orientations are closely tied with questions of motives; indeed, motives “are assigned with reference to our orientation in general” (31). Burke understands motives as “shorthand words for situations” since they describe how we are likely to interpret and respond to a given situation (31). Orientations and motives thus describe the ways that we situate ourselves in the world; they contribute to the frameworks that give meaning to our experiences and guide our responses. Burke goes on to connect orientation and motivation with language in a passage worth quoting at length:

the question of motivation brings us to the subject of communication, since motives are distinctly linguistic products. We discern situational patterns by means of the particular vocabulary of the cultural group into which we are born. Our minds, as linguistic products, are composed of concepts (verbally molded) which select certain relationships as meaningful. Other groups may select other relationships as meaningful. These relationships are not realities, they are interpretations of reality—hence different frameworks of interpretation will lead to different conclusions as to what reality is. (35)

Orientations, motives, and vocabularies inflect each other in a cyclical fashion: our vocabularies and uses of language shape our orientations toward and interpretations of the world, and our orientations and interpretations shape the way we use language. Orientations, and the vocabularies that embody them, mediate our understanding of reality and our interactions with the world around us. In this sense, orientations are procedural; they give shape to the logics that structure our experience. Like procedures, orientations “constrain the types of actions that can or should be performed in particular situations” (Bogost 4); they constrain the processes of interpretation and response through which we give meaning to reality and experience and respond to the world.

Burke examines the links between orientations and language at this abstract and individual level in order to consider how these orientations interact with and comprise broader social, cultural, and historical attitudes, and it is with this point that we can return to our concern with rhetoric’s procedures. In Attitudes Toward History (1937), Burke reads social and historical attitudes alongside literary forms, noting how “each of the great poetic forms stresses its own peculiar way of building the mental equipment (meanings, attitudes, character) by which one handles the significant factors of his time” (34). In this sense, literary forms provide another embodiment of procedurality, privileging certain orientations and attitudes over others and framing the perspectives through which we experience the world. Burke discusses a range of literary forms, from tragedy to the grotesque, but his account of the comic frame lends itself best to the search for rhetoric’s procedures. If, as suggested above, rhetoric cannot be defined by a particular set of processes but instead requires an ability to shift and negotiate between processes and logics, then no particular orientation or frame could account for the complexity of any given rhetorical situation. For Burke, the comic attitude embodies this perspective, as it focuses on the limitations of any specific orientation. From the comic perspective, “people are necessarily mistaken” since “every insight contains its own special kind of blindness” (41). Recognizing the limitations of our perspectives is the farthest that “[t]he progress of humane enlightenment can go,” and this recognition allows us to “complete the comic circle, returning again to the lesson of humility that underlies great tragedy” (41).

In this sense, the comic attitude is characterized less by a specific orientation, logic, and set of processes than by an awareness of the limitations of procedural thinking, an awareness that encourages a sense of humility. This is not to say that we can avoid procedurality entirely, that we can experience the world outside of a particular logic or frame of reference. Nor is the necessity of procedurality in our orientations and attitudes necessarily a bad thing; as Bogost notes, “[w]hile we often think that rules always limit behavior, the imposition of constraints also creates expression” (7). Rhetoric, however, demands the ability to balance the necessity of constraints against the recognition of these constraints as situated and contextual. In this balancing act, we must be able to recognize the limitations of our own perspectives and to make room for others. The comic attitude describes this meta-perspective, and it is thus no surprise that Burke calls it the “attitude of attitudes” (n.p., third page of “Introduction”).

To reiterate, Burke’s account of orientations and attitudes suggests a sense of procedurality; these frames describe the logics through which we process and give meaning to our experience. The interplay of orientations, attitudes, language, symbolic activity, processes, and logics characterizes rhetoric’s shifting and unstable ground. To the extent that our practice of rhetoric entails a responsibility to account for this shifting and unstable ground, rhetoric’s procedures must necessarily be in flux. The comic attitude provides a way of accounting for this flux by describing a procedurality that questions and seeks the limits of any framework for understanding the world. Burke’s notion of identification parallels this understanding of attitudes; identification suggests a similar sense of rhetoric as procedural, and it has its own version of the comic attitude. Although a closer look at identification will retrace some paths, it will also provide a more detailed account of the ways that procedurality is embedded within language and symbolic activity generally.

Burke considers identification in A Rhetoric of Motives (1950) and, as noted by Bogost, uses this concept to expand on the traditional association between rhetoric and persuasion: “You persuade a man only insofar as you can talk his language by speech, gesture, tonality, order, image, attitude, idea, identifying your ways with his” (55). In this sense, identification includes persuasion but also suggests more generally the ways that people identify with one another and become “consubstantial,” sharing “common sensations, concepts, images, ideas, attitudes” (21). In identification, an individual becomes “both joined and separate, at once a distinct substance and consubstantial with another” (21). For Burke, this interplay of identification and division describes the scene of rhetoric:

In pure identification there would be no strife. Likewise, there would be no strife in absolute separateness, since opponents can join battle only through a mediatory ground that makes their communication possible…But put identification and division ambiguously together, so that you cannot know for certain just where one ends and the other begins, and you have the characteristic invitation to rhetoric. (25)

The scene of identification and division recalls Burke’s earlier attention to the scene of differing interpretations, orientations, and attitudes. Both scenes offer an invitation to rhetoric, to communication, and, returning to an earlier quote, to “the use of words by human agents to form attitudes or to induce actions in other human agents” (41). Furthermore, just as with orientations and attitudes, we cannot locate ourselves outside of the scene of identification and division. We are already exposed to this scene, and we navigate through it according to our orientations and attitudes.

For Burke, the process of identification occurs through language and symbolic activity; language and symbols serve as the sites where individuals negotiate their shared and differing ideas, attitudes, concepts, beliefs, etc. Burke clarifies this process of negotiation by classifying language according to three categories: positive, dialectical, and ultimate terms. Positive terms “name par excellence the things of experience” (Rhetoric 183); dialectical terms “refer to ideas rather than to things” (185). Burke describes the dialectical order with reference to parliamentary conflict, suggesting a scene of various voices, ideas, attitudes, and goals, each vying for representation. This scene helps explain the nature of ultimate terms: “The ‘dialectical’ order would leave the competing voices in a jangling relation with one another…but the ‘ultimate’ order would place these competing voices themselves in a hierarchy, or sequence, or evaluative series” (187). The notion of ultimate terms helps clarify the ways in which symbolic activity has attitudes and orientations embedded within it. Ultimate terms orient our understanding of the world in particular ways; they suggest the logic according to which we assign value to things and through which our experience takes on meaning. As terms that place competing voices in an evaluative series, they organize dialectical terms and positive terms, arranging them into a meaningful system. To return to the example of the parliamentary scramble, different ultimate terms suggest different parliamentary outcomes, different laws, and different approaches to government. A debate over such dialectical terms as “limited government” and “the right to universal health care” involves appeals to conflicting ultimate terms. Even positive terms like “operation” and “medicine” get organized and prioritized in different ways according to various ultimate terms.

As language that embodies attitudes and orientations, ultimate terms in turn embody a sense of procedurality. Such terms contain within themselves the logic for evaluating and organizing other terms, and different ultimate terms suggest different logics and processes for such systematizing. If we bring the comic attitude to bear on the notion of ultimate terms, the “ultimate” status of such terms gets called into question, unsettling any given hierarchy or evaluative series. For Burke, “[a]ny such ‘unmasking’ of an ideology’s limitations is itself made from a limited point of view” (Rhetoric 198), leaving no ultimate of ultimate terms. But rather than allow relativism to rule the day, Burke instead suggests a practice of “relationism” that aims “to build up an exact body of knowledge about ideologies by studying the connection between these ideologies and their ground” (198). In other words, “each such limited perspective can throw light upon the relation between the universal principles of an ideology and the special interests which they are consciously or unconsciously made to serve” (198). Such examinations of the links between ultimate terms, the ideological systems they organize, and the interests that ground them contribute to a “sociology of knowledge” (199), that is, a knowledge of the limitations and situatedness of any particular perspective, ideology, or ultimate term. This knowledge would not aim to do away with ultimate terms; after all, “if your method for eliminating all such bias were successful, it would deprive society of its primary motive power” (201). Ultimate terms – as well as attitudes and forms of procedurality generally – impose constraints on us, creating and limiting the range of possibilities that our thoughts, actions, beliefs, and other interactions with the world can become. Such constraints motivate particular experiences of and responses to the world. Again, for Burke, rhetoric does not aim to move beyond such constraints but rather to recognize the limitations and implications of any particular set of constraints (attitudes, ultimate terms, etc.). In addition to the comic attitude, Burke’s notion of the sociology of knowledge gestures toward another way of situating a set of constraints; it describes a process of finding the limits and the ground of any particular knowledge and the perspective that generates it.

In “Finitude’s Clamor; Or, Notes toward a Communitarian Literacy” (2001), Diane Davis advocates for a similar recognition of our limitations in the game of rhetoric. Her interest in procedurality focuses primarily on hermeneutics, processes of interpretation and meaning-making, of apprehending and comprehending the world. To bridge this with Burke, we could say that any hermeneutic act occurs with reference to a particular orientation and makes available (and shuts down) certain possibilities for identification. For Davis, hermeneutics necessarily involves an engagement with an other that can never be fully grasped or represented. There are different ways we could talk about or frame this other – as a text, as a person, etc. – but the key point for Davis is the way that such framing devices will always fail to account for the radical alterity and absolute otherness of the other. Our understanding and interpretation of the other is always conditioned and constrained by our orientation toward it and by the procedures we enact to achieve this understanding. In other words, the other always exceeds any procedurality we could adopt to account for it. Moreover, we are already open and exposed to one another: “Communication can take place only among beings who are given over to the ‘outside,’ exposed, open to the other's effraction” (119). This emphasis on our finitude stands in direct contrast to the “myth of immanence” that informs much inherited thought on identity and subjectivity, a myth through which we understand ourselves as “a self-conscious self-presence” (120). In terms of the writing classroom, this myth leads to pedagogies that encourage students to see in themselves “the figure of the self-present composing subject” who “fancies itself ‘sufficiently discrete from the composing context to stand apart from it, observing it from above and commenting on it’” (121, embedded qte. from Sharon Crowley). Such a perspective fails to fully account for the ways in which our acts of communication are embedded and situated in the world, that we can never fully separate ourselves from the writing context to assume a posture of self-presence.

For Davis, rhetoric thus inherently involves a responsibility to others from whom we can never entirely extract ourselves and who we can never fully understand, despite our gestures toward immanence and hermeneutic desires to the contrary. Davis encourages us to read this responsibility as “an ethical imperative in our field today,” an imperative “to begin elaborating a kind of ‘communitarian’ literacy, a literacy which presumes first of all that writers and readers are in the world and exposed to others, a literacy that can read and write writing as a function of this irreparable exposure, of this irrepressible community” (122). A rhetorical practice that inscribes such a communitarian literacy would “foreground the writer’s radical ineffability and writing pedagogies that invite students to embrace precisely what divides them as what they share: their finitude, ‘the infinite lack of infinite identity’” (122, embedded qte. from Jean-Luc Nancy). Hermeneutic approaches to rhetoric, in which the writer attempts to read and interpret some aspect of the world (a text, an other, themselves, etc.), often fail to do justice to these notions of finitude and ineffability:

Of course, hermeneutics does involve a trip to the outskirts, breaking with fantasies of immediacy and issuing an interpretive imperative that owns up to the fact that no matter how close (near/intimate) the other is, communications between you have to traverse a static-filled distance. However, the instant a hermeneutic approach believes it has closed the distance, the moment the ‘guesswork’ lands on an understanding it deems ‘good enough,’ it outs itself as an internalist enterprise: Hermeneutics leads to certitude, Ronell notes in Stupidity, ‘only by turning away from the incomprehensible,' away from the inappropriable exteriority that sets it in motion to begin with. (129)

Davis’s discussion of hermeneutics thus parallels Burke’s discussion of language: for Burke, dialectical terms remain open and shifting, responsive to other dialectical terms, but ultimate terms read the world across one specific mode of procedurality, one specific hierarchy of terms and meanings; for Davis, hermeneutics can be an open process for traversing distances between yourself and the other, but this process can lead to a reification of the other and a belief that the distance has closed. Davis does not contest the practice of “interpretation; if it were not imperative, ‘we’ would not even be ‘here,’ struggling to work this through” (130). On the other hand, while not escaping procedurality, we have an ethical responsibility to recognize its limitations.

Toward this end, Davis posits a different sort of listening, one less interested in crossing the “static-filled distance” and more concerned with the static itself. This mode of listening “snap[s] into high perk at the first instance of any kind of incomprehensible ‘clatter,’” and it appeals to and engenders “posthermeneutic noise freaks” (130). Such noise freaks display a comic attitude of sorts; they are conditioned to see hermeneutic acts as necessarily mistaken, and they are more attuned to the transmissions that hermeneutic procedures fail to perceive. Of course, we could call into question the possibility of such a posthermeneutic position, the possibility of experiencing the world outside of a hermeneutic lens. After all, to hear “noise” is already to interpret the world, and to process this noise as anything else is to interpret ones experience even further. This leaves the noise freak in an unsettled posture, constantly in contention with herself and the act of assigning meaning to her experience. I find it helpful to invoke Burke’s notion of attitude here; perhaps the act of interpretation, unavoidable as it is, matters less than our attitude toward such acts. Perhaps we can best understand Davis’s noise freak’s posthermeneutic posture not as a position somehow outside of or beyond the act of interpretation but rather as a willingness, after the hermeneutic moment, to keep listening, through and for the noise.

With this in mind, to posit similarities between Burke’s comic attitude and sociology of knowledge and Davis’s communitarian literacy does not do full justice to the static-filled distances between them. And yet, Burke and Davis both encourage a rhetorical perspective that recognizes the necessity of procedurality – specifically hermeneutic procedures and processes of identification (and the attitudes, orientations, and uses of language that constrain such processes) – while simultaneously insisting on our responsibility to account for the situatedness and limitations of any given embodiment of procedurality. In this sense, rhetoric’s procedures undo, undercut, implode upon, reposition, and call into question themselves, recognizing the extent to which they are shaped by contexts that shift in time and by language that never fully grasps the other it gestures toward. The rhetorician never fully succeeds in this undoing; we necessarily fall back into procedurality, into hermeneutics and identification. Human activity will always be constrained by attitudes, orientations, and terministic screens. Nonetheless, we can adopt attitudes and engage in activities that disrupt and unsettle these constraints, exposing their limitations and opening possibilities for new orientations. With a clearer sense of (one understanding of) rhetoric’s procedures, we can return to the question of how videogames might embody these procedures.

Designing the Game That Undoes Itself

One of the main challenges and questions in designing a videogame/procedural rhetoric that accounts for the shifting and unstable nature of rhetoric’s procedures seems to be whether this instability can be captured within the game itself. We can imagine any number of conversations taking place around videogames that could discuss this instability, that could examine the procedural claims made by any particular videogame to better understand and to critique the perspectives that it describes, makes available, appeals to, and/or critiques. In this sense, any videogame could serve as the occasion for considering rhetoric’s shifting procedures. But what sort of procedural rhetoric could convey this instability within the game itself, giving players a richer sense for rhetoric’s complications and responsibilities?

In his Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture (2006), Alexander Galloway offers a vocabulary for discussing game action that can help us answer this question. For Galloway, “[w]ith video games, the work itself is material action. One plays a game. And the software runs. The operator and the machine play the video game together, step by step, move by move” (2). In order to more specifically describe the game action that occurs between operator and machine, Galloway introduces the terms “diegetic” and “non-diegetic” from literary and film theory, concepts that allow him to distinguish between diegetic game action that participates in the narrative within the game and non-diegetic “gamic elements that are inside the total gamic apparatus yet outside the portion of the apparatus that constitutes a pretend world of character and story” (7-8). These four terms – operator and machine, diegetic and non-diegetic – serve as poles and axes across which game action can be read. In this sense, all action related to game play involves some degree of operator and machine input and either contributes to the story within the game or does not. The intersection of these two axes creates four quadrants in which any gamic action can be located: diegetic machine actions, diegetic operator actions, non-diegetic operator actions, and non-diegetic machine actions. Diegetic machine actions include those aspects of a videogame in which the game itself generates action relevant to the story of the game. Galloway points specifically to those actions that happen in the game with no reference to input from the player (imagine starting a game of Frogger but not making any attempt to move the frog; cars, turtles, and logs will continue passing by) and those scenes presented within games, often between levels, that advance the story but do not require any action on the part of the player, momentarily rendering the player nothing more than a viewer. Diegetic operator actions include those normally thought of as game play and those most frequently considered by theorists of play. They are human, and they pertain to the successful advancing of the story and completion of the game. These are the actions that players perform within the context of the game itself, operating the controls to move through the game world.

Galloway’s consideration of the two forms of non-diegetic action will prove most relevant to the question of a videogame that aims at rhetoric’s procedures. Non-diegetic operator actions involve a player doing something outside of the narrative of a game. These actions “happen on the exterior of the world of the game but are still part of the game software and completely integral to the play of the game” (12). Hitting “pause” serves as the most basic example here: “The pause act comes from outside the machine, suspending the game inside a temporary bubble of inactivity” (12). There are other forms of non-diegetic operator actions such as cheats and game hacks, and taken together, such actions provide an “allegorical stand-in for political intervention, for hacking, and for critique” (12). Occurring outside the story of the game and enacted by players, non-diegetic operator actions create a space from which players can reflect upon and perhaps even change the game. Non-diegetic machine actions are those “performed by the machine and integral to the entire experience of the game but not contained within a narrow conception of the world of gameplay,” and they include “internal forces like power-ups, goals, high-score stats…but also external forces exerted (knowingly or unknowingly) by the machine such as software crashes, low polygon counts, temporary freezes, server downtime, and network lag” (28). Galloway clarifies the nature of non-diegetic machine actions with reference to two theorists of play, Johan Huizinga and Jacques Derrida: “With Huizinga is the notion that play must in some sense create order, but with Derrida is the notion that play is precisely the deviation from order, or further the perpetual inability to achieve order, and hence never wanting it in the first place” (30-31). Non-diegetic machine actions thus embody a sense of disorder, and more specifically a systemic disorder in which the machine/game system itself acts in such a way that does not fit with or contribute to the order of the game’s story. Having earlier linked Huizinga’s understanding of play to diegetic operator action, here Galloway connects Derrida’s notion of play, with its “certain sense of generative agitation or ambiguity” (28), to those aspects of games that interrupt and/or change the order of play.

Taken together, the two non-diegetic forms of game activity suggest a sense of disruption, a break from the game’s regular storytelling mode, and these non-diegetic moments create a possibility space outside of the normal experience of the game. In our discussion of rhetoric’s procedures above, we found a similar notion of disruption, a call for interrupting those processes of identification and interpretation that inevitably fail to account for a rhetorical situation in its entirety. Following this line of thought, it seems possible to suggest that rhetoric’s procedures are in some sense non-diegetic. To draw out the analogy, let’s recall Davis’s notion of the myth of immanence, a myth that supposes that we as individuals are in some sense self-contained and that we can achieve some sort of self-presence. For Davis, we never achieve this self-presence or containment; we are always exposed to and situated within the world, a world made up of others who are also exposed. The diegetic mode of game action lends itself to a similar myth of immanence, a sense in which the action and the story within the game is self-contained. Galloway’s attention to the non-diegetic aspects of game play remind us that the game world is not self-contained, that players can stop the normal flow of the game and even hack into it, and that the machine itself can stop functioning all together or perform actions that do not maintain the integrity of the game world.

The diegetic action of the game is thus exposed to the non-diegetic, open to its interruptions. Continuing with the analogy, if responsible rhetoric demands a mode of procedurality that interrupts itself, that recognizes its own limitations and seeks out new perspectives and processes, then it appears that a videogame/procedural rhetoric attempting to embody rhetoric’s shifting and unstable procedure’s could benefit from somehow incorporating the non-diegetic into its own diegetic action. In other words, the ways in which rhetoric’s procedures challenge the very notion of procedurality, seeking out the limits of any particular process, resembles the ways in which non-diegetic action exposes the limits of diegetic action; this resemblance in turn suggests the possibility of designing a videogame that exploits non-diegetic elements in order to advance its own procedural rhetoric.

Now, I want to be careful here. For Galloway, these different modes of gamic action are not rigid: “They should in no way be thought of as fixed ‘rules’ for video games, but instead are tendencies seen to arise through the examination of particular games” (38). In this sense, we are not ready to say that non-diegetic action is synonymous with critique and that diegetic action merely reinforces a status quo. Similarly, I do not want to suggest that diegetic action is somehow incompatible with rhetoric’s shifting ends or that non-diegetic action is somehow inherently ethically charged. Ultimately, this trip through Galloway’s consideration of the diegetic and non-diegetic actions within videogames serves not as an attempt to equate certain game experiences with certain attitudes in order to establish certain principles across the board for designing a rhetoric videogame, but rather as an opportunity to consider one particular approach to game design, specifically the approach we at the Digital Writing and Research Lab took with our game.

In Rhetorical Peaks, we have attempted to design a playing experience that allows students to engage with the notion of procedurality itself, considering and questioning rhetoric’s procedures and simultaneously examining their own attitudes, interpretations, and identifications. The game design relies on the interaction of diegetic and non-diegetic actions and the tension between these two modes in order to work toward these ends. Recall that, according to Galloway, in the non-diegetic space of a game – when the game is on pause – players have the opportunity to reflect on the game and even to change it, to cheat it, and to hack it. We could also say, to design it. Rhetorical Peaks invites players to explore the non-diegetical space of the game, acting simultaneously as players and designers. To allow for this double perspective, the game includes a story, but the story does not end within the context of the game; the game encourages players toward a particular end, but it does not guide players toward this end through specific rules and processes. Instead, players must provide the rules. They must choose the processes they complete in response to the game, and these processes in turn shape the game’s narrative.

In terms of the game’s diegesis, players are presented with the mysterious death of Lisa Sophist, the best speaker in a town dedicated to rhetoric. Given that the citizens of Rhetorical Peaks had always been able to work out their differences amicably, through communication rather than violence (setting aside for the moment a Derridean conflation of the two), Lisa’s homicide/suicide (we don’t know which) presents a unique threat to their sense of community and trust. The player enters into the story to help the town restore a sense of trust, but this does not necessarily involve solving the mystery of Lisa’s death. This aspect of the game was inspired by Twin Peaks. In their original conception of the television series, creators David Lynch and Mark Frost did not intend to solve the central murder mystery, at least not for a long time. As David Lynch explains it, “[t]he mystery of who killed Laura Palmer was the foreground, but this would recede slightly as you got to know the other people in the town and the problems they were having…The project was to mix a police investigation with the ordinary lives of the characters” (Rodley 158). Given the show’s focus on the community around the tragedy, Twin Peaks became – according to Robert Engels, a writer for the series – “a TV show about free-floating guilt” (Rodley 156). This notion of free-floating guilt conveys a sense in which everyone in town was responsible for the death of Laura Palmer in some way or another, and it parallels our earlier concerns with rhetoric’s procedures. Burke’s comic attitude recognizes that our perspectives are necessarily mistaken; Davis’s account of communitarian literacy notes that our hermeneutic appropriations of an other always fail to do justice to the other. Procedurality thus inherently suggests a sort of free-floating guilt, a sense in which the limitations of our orientations, identifications, and interpretations make us guilty before one another, the others to whom we are responsible. By evoking this aspect of Twin Peaks, the story of Rhetorical Peaks confronts players not only with a mysterious death but also with a more general condition of responsibility and constraint. In this sense, the game encourages players to look beyond Lisa’s death and toward the community of Rhetorical Peaks itself.

Different versions of the game allow players to participate in and contribute to its story in different ways. In the Flash version of the game, players take on the role of rhetoric students who stumble upon the town of Rhetorical Peaks and its recent tragedy. Players have the opportunity to interview three non-player characters (NPCs), each of whom offer a perspective on Lisa’s death, on each other, and on the town generally. Once the player has obtained all of the available evidence and testimony from these NPCs, the game itself stops, and the story can only be resolved outside of the game world itself. Here’s where (we hope) the game gets interesting. Having no specific or predetermined end state and no rules that dictate what players must do with the evidence they find, Rhetorical Peaks does not embody a procedural rhetoric. It does not guide players through a particular logic or set of processes, and thus it does not make claims about how the world works. Instead, it confronts players with an open-ended situation, and the outcome depends entirely on the processes they choose to enact. Since players will most likely be playing the game in a classroom setting, it is up to the class to determine what to do next. The game lends itself to procedures frequently taught in rhetoric and writing classes, processes related to rhetorical analysis and argumentation. The NPCs provide enough evidence for students to make several different arguments about the cause of Lisa’s death, and classes can consider which NPCs they find most trustworthy and authoritative. So, the game can be used to practice using more traditional rhetoric skills and concepts.

Professor Gorgias, Flash version.

At the same time, the game opens the possibility for a much broader consideration of procedurality. At the beginning of the Flash version, the town’s ambassador, Postumius Terentianus, tells players that their goal is to help the citizens of Rhetorical Peaks trust one another again, but the player is not told how this is supposed to happen.

Postumius Terentianus, Flash version.

We can imagine any number of processes that could be enacted toward this end, any of which could be discussed in greater detail in class, but no particular process guarantees the restoration of trust. Players can make claims about the cause of Lisa’s death, employing the procedures of analysis and argumentation, and the class can try to reach a consensus, but Postumius’s challenge continues to haunt the possibility space of the game. Rhetorical Peaks thus encourages players to see any response to it as necessarily limited, necessarily mistaken. This can make for a frustrating gaming experience, working against players’ expectations that any given game will end and will more or less tell you how to play it. Furthermore, the Flash version of the game does not satisfy the question posed at the beginning of this section as to whether a game’s procedural rhetoric could embody rhetoric’s complex, contextual, and shifting procedures. Instead, the Flash version deliberately withholds a procedural rhetoric, asking the player to choose how to interpret and respond to the game’s story and to consider the implications of any particular procedural response. It provides an occasion for enacting different processes in response to the game’s situation and for discussing rhetoric’s procedures, but it does not embody them.

The Second Life version of Rhetorical Peaks moves toward embodying rhetoric’s procedures, and it does so by allowing players to take on the role of game developers to a much greater extent. At the time of this writing, we have just begun testing this version of the game, in my own Spring 2010 Writing in Digital Environments class. In this class, before entering Second Life, students designed characters for the game based on rhetors of their own choosing. The design process asked students to identify a model rhetor and to read and analyze a collection of their writings. Through this, students gained an understanding of the model’s own sort of procedurality, of their attitudes, orientations, and uses of language. The characters designed by students thus became an embodiment of a procedural rhetoric, making an implicit claim about how the models “work.” This design project thus presented students with an opportunity to negotiate different sorts of procedures, that is, the various attitudes, identifications, and interpretations at play among the model rhetors, the characters, and the students themselves. In Second Life, students have the opportunity to play the game as the characters they designed on an island created specifically for the game. At this point, the game has two rules: stay in character, and create a possibility space in which the town can regain a sense of trust. The playing/designing experience is thus simultaneously diegetic and non-diegetic: the diegetic unfolding of the game’s story requires players to constantly draw upon non-diegetic aspects of the game, specifically their character designs and the attitudes, values, beliefs, and uses of language of the model rhetors that inspired them. In other words, to play Rhetorical Peaks is to hack it.

Amphitheater, Second Life.

In terms of creating a possibility space for trust, players have a number of tools available to them. The primary form of game action for Rhetorical Peaks within Second Life involves communicating with other players, playing ones own character as others play theirs, but this communication can work toward any number of ends. For example, players can stage a trial, they can hold a town hall meeting to discuss how to respond to Lisa’s death, they can work together to create a memorial for Lisa – they can do anything that works toward establishing a sense of trust within the community. Together, the players must decide what procedures to enact, and this opens the game up to any number of possibilities. And yet, the players are constrained by their own character designs; they must be faithful to a particular procedural rhetoric. In this way, playing Rhetorical Peaks becomes intensely contextual, situated with reference to the specific acts of identification and interpretation made by the players interacting with and through their characters, their models, and each other. The playing experience becomes a simultaneous enaction of and reflection on rhetoric’s procedures, with the ground of the game constantly shifting according to the players’ input, their acts of play and design. The conversation that the Flash version of the game makes available thus becomes embodied in the game itself as players negotiate the limitations and constraints of their own characters, working through the open, noisy conditions of community.

Student-created memorial for Lisa, Second Life.

Through all of this, the intended end state of the game is not a particular outcome but rather a particular attitude, one characterized by the understanding that responsible rhetoric demands an ability and willingness to switch between different processes and logics, to seek out the limitations of any particular orientation – that rhetoric demands a recognition of the ways in which any particular reading of and response to the world is situated, contextual, and limited. As students play Rhetorical Peaks, their characters might not embody Burke’s comic attitude or Davis’s understanding of communitarian literacy, but the game encourages students to adopt these perspectives themselves. Again, the goal here is not to define principles of design for a rhetoric videogame or to put Rhetorical Peaks forward as an ideal embodiment of rhetoric’s procedures. To do so would go against the spirit of the game itself. Moreover, the game has many limitations of its own: students who play the Flash version of the game often enjoy it but ultimately find it confusing; while a certain degree of confusion seems appropriate and helpful when one is navigating rhetoric’s shifting terrain, it does not necessarily instill a comic attitude in players. For its part, the Second Life version of the game requires a substantial time commitment, with students designing characters over a period of weeks and facing a relatively steep learning curve just to get into and become comfortable with the space of Second Life itself. Rhetorical Peaks will thus likely not be the final voice on procedural rhetoric and rhetoric’s procedures, but it does encourage us to listen through and for rhetoric’s noise.

Notes

[1] In a recent blog post, Alex Reid responds to Bogost’s understanding of procedural rhetoric by noting the possibility of reading all texts as procedural: for example, “[b]ooks carry with them rules of behavior. Reading a book is a procedure, and a procedure that must be learned. Different books demand different procedures.” While I agree with Reid that processes inform our encounters with any given text and find my work here generally in line with his gesture toward a post-procedural rhetoric, Bogost’s distinction between the procedurality of videogames and other sorts of texts ultimately works for me. Both videogames and books (and any other texts) require certain interpretive procedures to be made meaningful, and they also require certain material procedures to be experienced at all. Books require our eyes to move across the page and our hands to turn those pages (recognizing here that other procedures become involved when we talk about audio and electronic books, programs that read books for people with visual impairments, etc.). With videogames, however, the material procedures necessary to experience the text are performed with reference to and through a computational system that requires certain inputs before it allows the player to experience certain aspects of the game. In this sense, you have to complete certain processes to advance to level four in your game, but you can skip to chapter four in your book anytime you want. Recognizing the ways in which all texts require procedural interactions is important, but it can also be helpful to recognize the ways in which unique texts require unique modes of procedurality. I do not think Reid is unsympathetic to this idea but rather wants to look at the situation from the other side.

[2] I cannot do justice here to the range of possibilities that the concept of procedural rhetoric makes available, but I would like to gesture toward some of the ways it has been used. At the time of this writing, two current examples of the concept of procedural rhetoric at work come to mind. Mark Sample has organized a panel for the 2011 MLA conference titled “Meaning Making and Procedural Rhetoric in Casual, Art, and Indie Games” that “[e]xplores the cultural meaning of critically dismissed” games. Also, Jim Brown argued on his blog that Bogost’s concept of procedural rhetoric offers new possibilities for a rhetorical approach to software studies, asking how “the rhetorical texts (software) created by programmers shape the rhetorical actions (writing, gaming, or the ‘traversing’ of cyberspace in Aarseth’s words) of by [sic] digital rhetors.”

[3] Of course, there are a great many concerns and conversations about rhetoric’s procedures (the processes underlying different reading, writing, teaching, and theorizing practices) and their ultimate goals (persuasion, identification, consensus, perspective-shifting, civic engagement, etc.). My hope here is to point to assumptions about rhetoric shared by many different camps that complicate our ability to describe rhetoric as a fixed set of processes.

[4] It is worth commenting on the two different uses of “rhetoric” here. In its more general usage, rhetoric can designate any sort of symbolic activity, regardless of its assumptions. In this sense, my particular rhetoric need not be concerned with context or the instability of language at all. On the other hand, we could say that these concerns inform any and all rhetorical situations regardless of our recognitions of them, and we could go a step further and say that we have an ethical obligation to account for these concerns in our practice of rhetoric. This essay will consider both perspectives on rhetoric – the general and purportedly neutral usage as well as the ethically charged sense – in order to describe how procedurality intersects with rhetoric generally as well as to examine rhetoric’s responsibilities.

[5] The actual development of the game did not proceed according to such a straightforward narrative; we did not think through the entire question of Rhetorical Peaks’s procedural rhetorics before we designed the game. Rather, we made particular design choices and reflected on them over time, sometimes realizing the full implications of these choices

long after they had been put into place. By offering a narrative that suggests the development from a particular theoretical framework toward a specific game design, I hope to offer a lens through which we can read the question of rhetoric and procedurality – and Rhetorical Peaks as a response to this question – rather than a chronological history of the game itself.

Works Cited

Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007. Print.

Brown, Jr., James J. “A Role for Rhetoric in Software Studies, Part 2.” Clinamen. N.p. 17 Jan. 2010. Web. 1 May 2010. <http://clinamen.jamesjbrownjr.net/2010/01/17/a-role-for-rhetoric-in-software-studies-part-2/>

Burke, Kenneth. Attitudes Toward History. Third ed. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1984. Print.

---. A Grammar of Motives. 1945. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1969. Print.

---. Permanence and Change: An Anatomy of Purpose. Third ed. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1984. Print.

---. A Rhetoric of Motives. 1950. Berkeley": Univ. of California Press, 1969. Print.

Crowley, Sharon and Michael Stancliff. Critical Situations: A Rhetoric for Writing in Communities. New York: Pearson, 2008. Print.

Davis, Diane. “Finitude’s Clamor: Or, Notes toward a Communitarian Literacy.” College Composition and Communication 53.1 (2001): 119-145. Web. 11 July 2009. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/359065>

Galloway, Alexander. Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2006. Print.

Rodley, Chris, ed. Lynch on Lynch. London: Faber and Faber, 1999. Print.

Reid, Alex. “post-procedural rhetoric and serious games.” digital digs. N.p. 11 March 2010. Web. 1 May 2010. <http://www.alex-reid.net/2010/03/postprocedural-rhetoric-and-serious-games.html>