- Although a significant body of work has been published on the relative benefits of integrating the Internet into composition classroom pedagogy, Marcia Curtis and Elizabeth Klem have lamented the fact that "despite an almost pervasive acknowledgement of the potential benefits of research focused, not on 'texts' exclusively but on the 'contexts' in which writers produce them, relatively little ethnographic--that is, true contextual research--has appeared, in composition studies generally and computer based-composition studies especially" (157). More specifically, few studies have been published on the benefits of the World Wide Web as a research tool for students despite the fact that the "Web is providing documents and resources that simply do not exist in any other form, resources that would be too expensive to publish on paper or CD-ROM. Right now--and not in some distant future--doing research without looking for resources on the Internet is, in most cases, not really looking hard enough" (Dobler 69, Dobler's emphasis). By failing to train our students to use the World Wide Web for their own research we are not only teaching them that it is okay to "not look hard enough," we are omitting from our pedagogy a system that encourages a new way of reading information and that engenders critical thinking and writing. In this essay, then, I will discuss the kind of work that becomes possible in a course using the World Wide Web, while illustrating the limitations of a pedagogy that does not take into consideration the importance of training students to look critically at the information on the Web before they are sent off to do their own research. It is the training, after all, that will give students the ability to navigate the Web's serpentine pathways and read Web pages critically.

- One of the focuses of the course discussed below, the Kosovo Crisis, is perhaps dated when one considers the military conflicts that have taken place since. Indeed, I have taught courses based on the one described below, using the attack on Afghanistan in 2002 in place of Kosovo, and envision using the war on Iraq in the future. What made the Kosovo crisis so compelling for study at the time was that it was the first major military conflict to be reported on the Internet, and as a result became an ideal topic for consideration by students. The theoretical approach to the study of Web pages presented below is, however, still relevant today (perhaps even more relevant today) because of the ever-growing role the Internet has in the lives of our students--both in and out of the classroom--and the growth of the Internet as a medium for news and opinions that differ from the those portrayed in mainstream media outlets.

- Teachers and administrators hesitate in incorporating the World Wide Web into their classes and their Writing Program pedagogies because they just aren't sure how to tame it: "One of the biggest problems of the Internet from a teacher's perspective is that it's not just the amount of information that is daunting to the students; it's also the extreme variety. Pornography has been represented as the great danger to children who use the Internet, but a far greater danger is the amount of misinformation on the Internet" (Faigley 134). James Strickland concurs: "On the Internet, fringe groups and academic scholars have the same standing; everyone looks the same" (91). To battle researchers' concerns over site validity, librarians and Internet scholars have published online articles that outline criteria for evaluating web-site validity. Minnesota State University at Mankato, for example, has a page that lists seventeen Web pages that discuss site validity. Robert Harris of Vanguard University of Southern California has an excellent site that discusses in detail what he calls "The CARS Checklist (Credibility, Accuracy, Reasonableness, Support), [which] is designed for ease of learning and use. Few sources will meet every criterion in the list, and even those that do may not possess the highest level of quality possible. But if you learn to use the criteria in this list, you will be much more likely to separate the high quality information from the poor quality information" (par. 8).

- These sites and their criteria are helpful for educating students about what is a good and bad site, but they do not teach students what to do with information that is deemed "unreliable." Motivated by a desire to complicate my students' research and to advance their critical thinking, I trained students in a section of the upper level composition class (Expository Writing II) I developed while an instructor at Rutgers University, "War & Ethics," to use the World Wide Web to find material on their subjects by using the Kosovo Crisis as an example. The technology allowed us to gain immediate access to a range of materials--Serbian representations of themselves, the ethnic Albanians, and the NATO forces--unavailable in any traditional library. As a system for disseminating information, the World Wide Web is attractive for students and researchers, but this vast information network also makes the research community nervous precisely because there's no ready way of determining whether the information on the Web is biased. Prior to the Kosovo Crisis, I too was skeptical of my students' capacity to conduct Web research because of the vast amount of misinformation presented online. By teaching students to look only at the information presented on the page and not critically at how the information is being presented, we are taking away an integral part of Web research, which is reading the page itself. When students begin to read web pages, when they are able to look critically at the politics behind who is presenting the information, all web pages--from pages that deny the Holocaust, to individual home pages, to BBC News reports, to journal articles found at Proquest or JStore--become useful (as opposed to reliable). In other words, reading Web pages rhetorically allows students to consider not only what gets said, but also how it gets said.

- In the following discussion I will argue that by uniting Internet technology, the composition classroom, and student research, it is possible to develop a truly dialogic pedagogical practice that fosters critical thinking and writing. Gail Hawisher and Cynthia L. Selfe assert that "our classrooms--and those of most of our colleagues--seem to be populated by students who see little connection between traditional literary education and the world problems they currently face--the continuing destruction of global ecosystems, the epidemic spread of AIDS and other diseases, terrorism, war, racism, homophobia, the impotence of political leaders and the irrelevance of political parties" (vii). Barbara B. Duffelmeyer furthers the call for creating more critically aware students by focusing on the relationship students should have with technology: “Our pedagogy, to be critical in [a] potentially valuable way, needs to provide an occasion for students to reflect on and articulate their relationship to digital technology, the forces that influenced the formation of that relationship, and the ways that they might develop some agency within the parameters of that relationship, thus opening the way for them to develop the more complicated and mature positionings relative to technology that computers-and-composition scholars advocate” (2). One way to bridge the chasm between the traditional goals of a university liberal arts education, urgent contemporary issues, and a lack of critical thought about technology is by advocating the use of Web sites--both "reliable" and "unreliable"--which can then enable students to think more critically about issues of relevance to contemporary society.

- Expository Writing II at Rutgers University requires students to write two short essays (4-7 pages) that serve as an introduction to the prominent theories on the section topic, a research proposal, an annotated bibliography, and three rough drafts and a final draft of a research paper. The research paper involves a substantial response to a chosen topic in keeping with the subject matter of the course. The essays students write ask them to frame case texts with theoretical texts with the goal of coming to their own conclusion not about the texts themselves, but the ideas the texts introduce. "War & Ethics" was born out of my desire to complicate the ethical questions students were tackling in my section, "Interpreting the Holocaust," and to explore what I was beginning to see as student interest in war-related subjects. Students read selections from the following texts: The Ethics of War by A.J. Coates, The Guns of August by Barbara Tuchman, Just War: Principles and Cases by Richard J. Regan, and a Kosovo Packet created from materials taken from the World Wide Web that corresponded to the then current Kosovo Crisis. The texts and class discussions attempted to battle students' tautological conclusions that "war is bad," and asked them to come to their own individual conclusions about whether just war theory can be used in order to justify going to war or acts that are committed during war. Their own interests led them to such research topics: "Communism and the Domino Theory: Propaganda and President Johnson's Attempt to Justify American Involvement in Vietnam," "Killing One's Own Forces: Agent Orange and the United States Violation of Proportionality in Vietnam," "Japanese Biological Warfare: The Emperor Ideology and the Japanese Justification for Human Experimentation," and "Sitting on Top of the World: George Bush's Manipulation of Just War Theory During the Gulf War as a Means of Gaining Global Power." For each of their essays, it was the use of the World Wide Web that allowed the stronger students to take their arguments to extraordinary rhetorical levels and the weaker students to add new information they otherwise would not have found. Their Web training came from the work they did with the Kosovo Crisis.

- The Kosovo Packet I put together for the summer section of "War & Ethics" was divided into three sections: American Media Reporting, Pro-Serbian Media Reporting, and War Crimes Opinions. The packet's structure immediately generated discussion on the veracity of the media in depicting events and led students to introduce their own ideas on the way media shapes reality and how citizens' opinions are manipulated by what they see on TV, hear on the radio, and, now, read on the Web. Their ideas early in the semester, however, stopped with the understanding that the manipulations take place; they were not yet able to understand the implications of the manipulations. Anticipating that problem, I included articles from the New York Times (for example, "NATO Refocuses Targets to Halt Serbian Attacks on Albanians in Kosovo" and "NATO Said to Focus Raids on Serb Elite Property") that, if looked at closely by the class's frame texts, would encourage students to look critically at NATO's actions and the dangers of listening too closely to media without considering the ethical implications of war-time actions. I also included articles and images from pro-Serbian pages that would begin to challenge the way students read Web pages and hopefully increase their critical thinking about the situation in Kosovo, the role America was playing, and the function of the World Wide Web as a system for disseminating information. For example, when we began to discuss images that depict swastikas on NATO flags (See Figure 1 below), students only saw the images as the Serbians' way of saying "The U.S. and NATO are bad"; they were not yet able to complicate their ideas and look at the implications of such manipulations on the way we view history, its potential for desecration, and what it actually says about the individuals who generated the image. That is, students were not yet able to refocus their critical thinking from what was on the page to what the page itself was saying.

- In order to jump-start my students' critical thinking, introduce them

to more complex rhetorical forms of discourse, and move them from having

ideas about the texts to using the texts for their own ideas, my second

assignment asked the following:

In response to the attack on Aleksinac and the many others which have resulted in what NATO calls "collateral damage," the Serbian media and others have been calling NATO and their attacks "indiscriminate" (Cockburn 1) "massacre[s] . . . [on] civilian targets important for [the] normal life of the citizens of Yugoslavia" (Serbia 1). The attacks have also produced reports that attempt to bring the deaths down to the level of the individual and propaganda that attempts to equate NATO with Nazis.

For this essay, then: Considering the abstract theories of discrimination and proportionality elaborated upon by Regan and the representation of NATO attacks by the U.S. media and pro-Serbian web pages, I would like you to come to your own conclusion about the morality of the NATO bombing of what they are calling "war-related targets."

Richard Regan's essay "Just War Conduct" from Just War: Principles and Cases served as our second frame text; A.J. Coates's "The Just War" had introduced students to the just war theory in the first sequence, where they were asked to consider war theory in relation to the beginning of World War I. In the second sequence, students began looking at the more complex and often evasive jus in bello theories of discrimination and proportionality. According to the principle of discrimination, "just warriors may directly target personnel participating in the enemy nations wrongdoing [(which he later calls "war-related targets")] but should not directly target other enemy nations" (Regan 87). Discrimination, as Regan sees it, "governs the subjective intention of those proximately and ultimately responsible for military actions. But the principle involves an objective component, namely, the projected target of military actions, and human agents in their full possession of their conscious faculties presumably intend the object of their actions. Therefore, the underlying focus of the principle of discrimination is on the nature of the target" (93). The principle of proportionality, on the other hand, understands that "bombing military targets, at least doing so on a large scale, will in addition to the destruction of those targets, almost inevitably result in the deaths of enemy civilians who are not participants in war-related activities" (96). The bombing, however, "will be morally permissible only if the importance of the military targets equal or outweigh the resulting deaths of ordinary citizens" (Regan 96). - Angelina (all student’s names have been changed) responded to

the assignment by arguing that although "NATO satisfies the principle

of discrimination by bombing valid military targets... the morality and

justification of these bombing[s] becomes questionable because as NATO

goes on, they start to violate proportionality." By making a distinction

between NATO's justification according to discrimination as opposed to

proportionality, Angelina needed to look specifically at the targets,

to take into consideration the relative importance of the target in relation

to the number of civilian deaths, and to consider what NATO's objectives

were in bombing that specific target. Each part of that analysis requires

more than merely looking at what the media is reporting; it requires an

analysis of the motives behind the reports and what the reports say about

the politics of those doing the reporting. After coming to the conclusion

that bombing bridges is justified because bridges are part of a country's

"industrial infrastructure," Angelina moves into a discussion

on the amount of "mistakes" NATO made in relation to the amount

of bombs and missiles used:

[W]hen one considers the amount of attacks that have been carried out, one must realize that NATO is bound to make a few mistakes. These mistakes are not what should be focused on, but rather, the number of attacks that have been carried out successfully. However, the Serbian media is trying to appeal to the reader's emotions by showing that people who were killed are real people with families and loved ones. They focus on the elderly and children to elicit sympathy from the readers. In an article that is titled "These are NATO Targets," a series of pictures with captions are shown of bombing sites and the people who were there. In one of these pictures the caption reads, "One of the civilian victims, a 73 year-old woman from Cacak, in central Serbia, killed in her yard during a NATO attack" (1). (See Figure 2 below.) By focusing on specific people and using pictures, they are showing that people who were injured and killed are everyday people and that they do matter. However, being that NATO was not aiming to hit these innocent victims, they were still justified in their bombing.

While Angelina may be correct in her argument about the justification of the attacks according to Regan's definition of the principle of discrimination, what interests me about this passage (and her essay as a whole) is not the argument itself (most students in the class came to similar conclusions) but how she engages her sources. When Angelina quotes a Serbian source, she quickly dismisses the report as sensationalist and biased, but she does not consider that the American reports could be biased in what they exclude. Her discourse, although critical of the Web pages, does not show the kind of critical thinking needed when using sources that might be deemed "unreliable"; she focuses not on the implications of the pictures, but on the pictures themselves. Her conclusion that the pictures "are showing that people who were injured and killed are everyday people and that they do matter" is an emotional not analytical response; she is discussing feelings and not implications, which is exactly what she is critical of the Serbian media doing. Angelina is a student who can use "unreliable" sources in her essay, but is not yet comfortable analyzing them or using them to help further her critique of NATO's actions. Later, when she finally does start to question America's motives for bombing specific targets, she does so by using American reporters and editorialists and not Serbian Web reports, which discuss in more detail the intended target, the target hit, and the amount of civilian deaths. Angelina never moves beyond dismissing sources when they are obviously biased against what she believes to be the correct political stance.

- Frida's essay, however, shows a student who is willing to use pro-Serb

media reports to help further her arguments, but is not yet sure how to

discuss the implications of her critique. After a paragraph in which she

comes to the conclusion that NATO is violating proportionality because

"foreseen civilian deaths indicate intentional attacks . . . with

low discriminative views," she states:

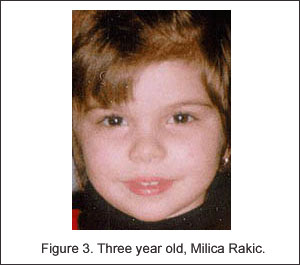

Regan makes the point that "the more disproportional the number of collateral civilian deaths, the more suspect will be the sincerity of a belligerent's claim that the intended target is military or war-related" (94). Therefore, it is not surprising that pro-Serbian propaganda also holds suspicion of NATO's actions and doubts that their tactics follow just war conduct. . . . Serbian propaganda alleges NATO of lying to the public and covering-up the many "accidents" which have killed many Serbs. The Nazi swastika ("Pictures" 1), symbolizing hatred and death, which they have placed on the flags of the countries that comprise NATO, gives a strong feeling of anger. The consistent reporting and photographs about infant (Cockburn 1) (see Figure 3 below) and elderly deaths ("These" 1), along with the danger caused to pregnant women, are used to grasp pro-Serbian attention. Through these remorseful reports and allegations of "false pretext for NATO military action" ("How" 1), the Serbs try to manipulate its public to gain support and show Americans the other side of the conflict. But the Serbs do not justify their action of "ethnic cleansing," since this is not seen in any of their reports. They only accuse NATO of the same thing they are doing, killing innocent people. However, whether or not most of these pro-Serbian articles were greatly exaggerated or some even false, it gave the opposite viewpoint. It raises questions whether NATO is being completely honest with the public, or hiding other "accidents" of war and actual counts of civilian deaths. Their justification for interfering in the Kosovo dispute and their choices for war-related targets may also be of some doubt.

On the one hand, Frida is unable to see the swastika's placement on NATO flags as more than an indication that the Serbs are angry with the bombing campaign, and does not consider in depth her ideas on the function of depicting the dead bodies of individual children and the elderly. Yet, unlike Angelina, she uses Regan's ideas to consider the effect these Web pages can have on her understanding of the events. While Angelina does not explicitly question NATO's motives based on the Serbian Web pages, Frida's conclusion that NATO's justification "may also be of some doubt" is an important interpretive move that illustrates, among other things, her ability to use Web-based materials to not only further the ideas in her paper, but to enhance her critical thinking about the events. Frida also understands that the reports do not focus on what they should be focusing on: justifying the Serb's actions against the Kosovars. Her ability to see past the rhetoric of the pictures to what they are not discussing indicates that Frida is ready to look critically at the politics behind a Web page and use what she deems "unreliable" material for the benefit of her ideas. Still, she is not completely comfortable using an alternative position to discuss the implications of her argument; if the Serb reports "raise[] questions [as to] whether NATO is being completely honest with the public, or hiding other 'accidents' of war and actual counts of civilian deaths," then how are we to ever fully understand events we view through the media? What does Frida's skepticism say about NATO's and the United States's altruistic image?

- Another student, Diego, begins to answer those questions toward the

end of his essay and accuses NATO of war crimes, calling their actions

"militaristic." After quoting William Rees-Mogg's assertion

that "NATO would grant 'permission to go after targets that in the

past had been rejected because attacking them had higher risks of collateral

damage'" (4), Diego states "NATO's actions had become skewed

and had lost the sense of discriminatory compassion with which it entered

this conflict; it had become more important to punish Serbia for not surrendering

as planned then it was to remain focused on simply defending the Kosovars."

As a result, according to Diego,

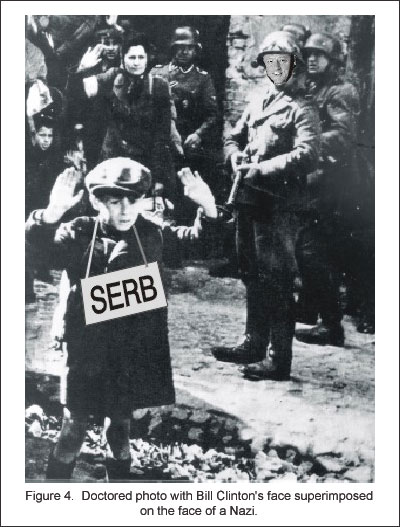

Such aggressive actions cannot be tolerated, especially from those who were self-proclaimed peacekeepers. Disgust against NATO has become well-defined in the media, specifically in anti-NATO propaganda reports. The internet has been a powerful tool for disseminating influential pictures and rhetoric to the masses. With the click of a few keys, one may easily access pictures of President Clinton depicted in Nazi apparel, pointing a gun at a Serbian child ("Pictures"). (See Figure 4 below.) Also, pro-Serb writers have done a thorough job of exploiting NATO actions and mistakes, in an attempt to sway the public opinion against its efforts....

While Diego understands the value of Web pages in discussing the Kosovo Crisis, he does not immediately discuss the implications of what he sees. Instead, he merely states that there is a doctored photo of a Nazi soldier and reports on NATO mistakes. His use of language-- "powerful for disseminating influential pictures and rhetoric to the masses" -- indicates a sensitivity to the Web pages' motives that we have not seen in Angelina and Frida. For Diego, the words and images on the pages do not exist in a vacuum; they mean something and have implications by virtue of their placement on a particular site.

- In the next paragraph, Diego discusses the implications of NATO's attacks

as a result of the information taken from pro-Serb reports:

NATO's actions are . . . presented as immorally equivalent to those of the Serb militia. As a people that support its leaders for being responsible decision makers on its behalf, we believe, as the media reports, that such accidental bombings are purely unfortunate and unintended consequences of an otherwise good plan. "The wrong building was attacked. It was a terrible accident. NATO deeply regrets loss of life . . . to any other civilians" (Gordon 5). However, as these accidents continued, one must start to wonder if responsible and moral choices are still be made by the powers that be. "A belligerent can hardly claim that it is fighting a just war if it wages war in a systematically unjust way" (Regan 98). Therefore, if we are inclined to believe that NATO's actions were morally negligent as the air strikes against Serbian forces became less discriminate and proportional, then we may certainly acknowledge that NATO is no longer acting in accordance with the pre-determined code of just war theory and may be subject to the same accusations of war crimes as those against the Serbs.

Unlike Angelina and Frida, who rely on pro-Serb web pages to support their own ideas and justly put that information in the middle of their paragraphs, Diego is using the information on the pages to help influence his interpretations of the events. By beginning this paragraph with a discussion of NATO's actions based upon his reading of the Serb Web pages, Diego is preparing the reader for his ultimate conclusion that NATO may be violating the principles it vocally claimed to be upholding. Here is a student who is willing to question NATO's actions because of what he saw in the pro-Serb media reports. With an understanding that NATO may not be as altruistic as it attempts to show, we read the Gordon quote with a tinge of cynicism--the statements in the quotes seem like they could be played over and over again for the media like a broken record--and are relieved when Diego confronts NATO and the morality of its bombing choices: "one must start to wonder if responsible and moral choices are still being made by the powers that be." By suggesting that NATO is guilty of the same war crimes as the Serbs, Diego shows his understanding that actions have implications, no matter what side you are on or how you are trying to represent the facts. Diego is a student who looks critically at the information he reads and considers the implications of his interpretation of what he reads, and without saying as much, comes to the conclusion that even what we think is a "reliable" source can be just as unreliable as one our political prejudices define as "unreliable." - The two main conclusions that Diego comes to--that information on Web pages has implications by virtue of its placement on a particular site, and that our own political and social prejudices essentially define what is and what is not a reliable source--are two of the most important understandings students should have when confronting the World Wide Web. Angelina, Frida, and Diego each show success with using the Web to further their ideas, think critically about a contemporary issue, and write more interesting papers; the Kosovo materials, however successfully they were used, added a unique critical level of engagement in each essay. The questions then become: What is gained by learning to read the Web rhetorically? and, when students eventually discover that much of the information they read is biased, what kind of research is left for them to do?

- During orientation for 102 teachers in the Writing Program at Rutgers in the fall 2000 semester, I introduced the Writing Program's new requirement that students use at least two online sources in their research papers. That source could be from an online journal, a journal article found on a Web database like Proquest, or from a Web site found using one of the many Web search engines. The problem, I told the instructors, was not going to be getting the students to use the Web, but training them to use the Web beneficially, so that they could find sources that would complicate their ideas in interesting ways. Handing out Robert Harris's CARS Checklist, I explained how important it is for students to be able to determine what is a valid source, but I also explained that it was up to the teachers to train the students how to look critically at the materials, just as I was asking my students to do in "War & Ethics." Before I could finish my presentation of the Orientation Packet, an instructor raised her hand and said what was most likely on the minds of many of the teachers in the room: "But, this means more work for me."

- In "Reading the Networks of Power: Rethinking 'Critical Thinking' in Computerized Classrooms," Tim Mayers and Kevin Swafford make the important point that "while the computerized classroom provides a space where critique is possible, it by no means guarantees that such critique will actually happen" (147). Instead, they believe that "Critical thinking and writing . . . do not simply happen as a result of technology, nor merely from savvy pedagogical use of technology, but rather from a specific type of pedagogical practice in relation to technology" (Mayers 147). What interests me about the instructor's statement read in conjunction with Mayers and Swafford's argument is not only the fear that lay behind her retort, but her immediate understanding that introducing a new course component would take a large amount of work on the parts of teachers and students, and a desire for administrators to change pedagogy as a direct result of the specific type of computer use in the classroom. Understanding that it is the training the instructor provides for the students and not the computer itself that gives students the ability to think critically is, I believe, essential when approaching the changes technology is foregrounded in composition classrooms, especially when considering the complexity of World Wide Web searches. When students are asked to use the World Wide Web in a research class, the focus of the class has to change from being a course that is just about research to a course that is also about critical analysis--critical analysis at the level of researching, reading, and writing.

- The first change I made to my course curriculum from the previous times I taught "War & Ethics" was to integrate the Web into their second writing assignment, as discussed above. By placing Web texts next to scholarly texts, students immediately saw that the Web was a valuable source of information--especially for contemporary issues--and depending on their chosen topic, any Web site could become useful. More important, however, is that students realize that material from the Web is worthy to be considered individually, discussed in class, and written about in their essays. In class we examined the ways that certain Web pages are trying to represent themselves and considered, with varied success, the implications of those representations. We discussed the implications of the images on the home page of www.kosovo.net of an injured child and the train NATO claimed to have accidentally hit as compared to the picture of a female Kosovar refugee with her children holding her head on Abcnews.com. (See Figures 5 and 6 below.) We also considered how to read essays by the editors of The Nation reprinted on a pro-Serb Web page, and how our own political prejudices factor into not only our readings of Web pages, but our discussions of them.

- In other words, in order to bring the Web into the classroom, I changed the way I structured my course so that students could not only read what's on the screen but consider the implications of what they were reading--before beginning their research. This critical work is different from the traditional work done with scholarly texts, where students read what is on the page but are not encouraged to question the motivations behind the rhetoric, the specific context in which the essay is placed, or how their readings help them to better understand society as a whole. When students critique Web pages, they are, in a sense, looking critically at popular culture; and no matter how necessary scholarly texts are to the research process, Web pages can better function as a way to diminish the distance students are feeling between their classrooms and society.

- That level of critical thinking enabled Diego's research paper, "Sitting on Top of the World: George Bush's Manipulation of Just War Theory During the Gulf War as a Means of Gaining Global Power," to burgeon rhetorically and critically as a direct result of the World Wide Web. In his essay, Diego uses a "psychological analysis of President Bush and its relevance to [A.J.] Coates'[s] definition of militarism to explain how information delivered to the public during the Persian Gulf War was manipulated by the administration." As a result, Diego argues that "we will see the false pretense of America's just war philosophy and a veering toward [a] militaristic strategy which, as explained by [Noam] Chomsky, helped to stake a claim as the dominant global superpower." Of Diego's eighteen sources, eleven were found on the World Wide Web by using as a search engine. Of the eleven sources, seven are speeches and/or transcripts from press conferences by George Bush found at The George Bush Digital Library; the remaining four are by Noam Chomsky, found at the Noam Chomsky Archive at ZNet, a multi-facetted online database/magazine "concerned with social change." What is important about Diego's sources, however, is not their number, but that 1) the Bush materials provided the necessary case material for his essay, materials which would have been extremely difficult to find in print sources, and 2) the Chomsky material enabled Diego to discuss his topic in terms of society as a whole and consider the greater implications of his ideas. Diego's essay, in other words, is not just about the topic; it is about the implications the ideas his topic engenders, and we see his greatest success when he is able to incorporate his understanding of his sources' biases as a way to further his own ideas.

- After coming to the conclusion that "President Bush knew well before

the start of air strikes that violence was an inevitable step in keeping

Iraq subordinate," Diego states:

Bush's eventual aggressive course of action was already pre-determined--he merely had to create the motive; this, of course, involved a tentative façade of effort to pursue peaceful means of resolution, which were later deemed ineffective. The president's withdrawal of non-violent alternatives for resolution is boldly stated in his January 16[, 1991,] address: "The world could wait no longer. Sanctions, though having some effect, showed no signs of accomplishing their objective" (Bush, "Address"). However, Chomsky challenges Bush's claim to last resort: "It was quite obvious in August [1990] that sections would be unusually effective . . . the sanctions were of absolutely unprecedented severity" ("An Unjust" sec. 2). He goes on the explain how the Allied coalition purposely de-emphasized the effectiveness of the trade embargo in order to justify forceful measures: "The U.S. and Britain . . . did not want sanctions to work. . . . [This] was combined with the explicit statement that there would be no negotiations. . . . The message is: the world is to be ruled by force. Not diplomacy, not economic power, but force" (sec. 2). Chomsky's idea becomes a clear possibility when one considers Bush's outrageous initial deployment of troops, much larger than any single figure from Vietnam. If true, President Bush's actions are clearly deceptive and exemplify characteristics of militarism. Specifically, the "militarist cannot remain indifferent to the fate of [his] enemies. Their annihilation becomes not just permissible but obligatory" (Coates 62). George Bush was not concerned with the ethical decisions; rather, he was striving for the accomplishment of selfish objectives, specifically satisfying his own militaristic ego among the other world powers, and removing Vietnam Syndrome from the rest of the skeletons in his closet.

The intertextual work Diego is doing in this paragraph is exceptional -- especially for a sophomore in college -- but what is important to notice is that the paragraph is structured around the ideas generated by materials found on the Web. Diego is using one of those Web sources--Chomsky--to look critically at another--Bush--and that criticism is placed in the context of a scholarly source, in this case, A.J. Coates. What I am most interested in is that Diego is not satisfied to take Chomsky's ideas at face value; he understands that Chomsky is a controversial figure (earlier he calls Chomsky "one of the most controversial linguistic scholars of this generation") and so must find support for Chomsky's arguments. When Diego explains that "Chomsky's ideas become a clear possibility," and begins the next sentence with the qualifier, "If true," Diego implicitly signals to the reader his understanding that Chomsky could be considered an "unreliable" source of information by some people, and as so must support his ideas. And when he needs that support and the support for ideas founded in Web materials, he brings in his scholarly source to cement his argument. - I would like to stress, in closing, that it is not the Web itself that has produced the critical thinking and writing shown in the above essays: the discussion of the essays has only served to illustrate the importance of training students how to use technology before they are ready to conduct educated research. The challenge for teachers of research writing courses is to develop coursework that will enable students to look critically at Web pages that are specific to their class so students will be able to understand that Web sources, after all, should not be categorized as "reliable" or "unreliable," but as "useful" depending on their own essay topic. When that shift takes place--when students are able to look critically at their sources’ biases--the important thing will be for them to be able to recognize the implications of biased sites. Once students recognize and then incorporate an understanding of bias into their essays, traditional research on their topics can still take place. When students are sensitive to the politics behind their subjects and their sources, and then incorporate that sensitivity into the essays, they create essays that discuss ideas, rather than set out to prove something that has most likely been "proven" before. In other words, the focus of the research is not about amassing information about a topic, but what new perspectives can be offered about a subject.

- Still the questions remain: Once students recognize that much of the information they read, hear, and see is biased in some way, what kind of politics is left for them? What is to become of our students when they leave our classrooms and head back into society with this new perspective? Are they to become cynical nihilists with little faith in institutions? Or, are they to become lost in a desire to consider all perspectives of an issue only to become disappointed when they realize that they cannot get past the knowledge that everything is still biased in one way or another? The questions seem bleak, and the answers distant--and are too complex to be considered here. However, if we are to bridge the chasm Hawisher, Selfe, and Duffelmeyer implore us to bridge, we must create students who are not only able to see the connections between contemporary society and the technological classroom, but are able to take what they learn in the classroom to re-think contemporary society. Considering the implications of that rethinking is important work that should be considered in some detail. What remains clear is that a research writing class whose goal is to create critical thinkers and not pragmatic researchers can give students the ability to enter into and re-evaluate contemporary society's many systems for disseminating information.

Just War Theory, Critical Thinking, and President Clinton

Dressed Up Like a Nazi

"But That Means More Work for Me!":

Rhetoric, Politics, and Training Critical Researchers